IS – No Respite

IS – No Respite

With the James Foley-video performance of 19 August 2014, the IS (Islamic State) has filed the first act of war against the Western world, changing radically the traditional communication strategies until then adopted by terrorist groups of Islamic origin. The so-called ‘beheading’ videos, short films of propaganda in which one hostage was beheaded, are not an invention of the Islamic State, they already existed in the early 2000s, released by the Jordanian terrorist Abu Musab al-Zarqawi. However, the IS was able to encode for these movies through specific formal choices and the special care aesthetic that distinguishes them, a real genre with its own structure and its rules.

If “the world-as-text has been replaced by the world-as-image” (N. Mirzoeff, Introduction to visual culture, Booklet, Milano 2005, p. 35), observing the world built by the IS-image we will see a system strongly rooted in the Western popular imagination (in the Anglo-American species) and governed by a tripartite system that includes:

1) the spectacle of death;

2) the dehumanization of the victims;

3) the desensitization of the viewer.

This system, perfected from time to time, is now immediately recognizable also thanks to a series of serial and recursive aesthetic characters, which hereafter will be brought to light through the sampling and analysis of three series of films made in a span between August 2014 and December 2015.

Jihadi John’s saga

The first attempt at horror serialization on a global scale is constituted by the video group, distributed by Al Hayat Media Center, that between August 2014 and January 2015, which saw protagonists Mohammed Emwazi – dubbed by the media Jihadi John -, and his victims.

Many common elements recur in each of the movies, which together make up what we might call a ‘saga in episodes’. First, the language (English, with subtitles in Arabic) gives precise indications on the main geographical destination of the video (the Western audience), while the short duration of each video (no more than 3 minutes, excluding the found footage) reduces the message to its essential elements, so that ensuring an immediate transmission.

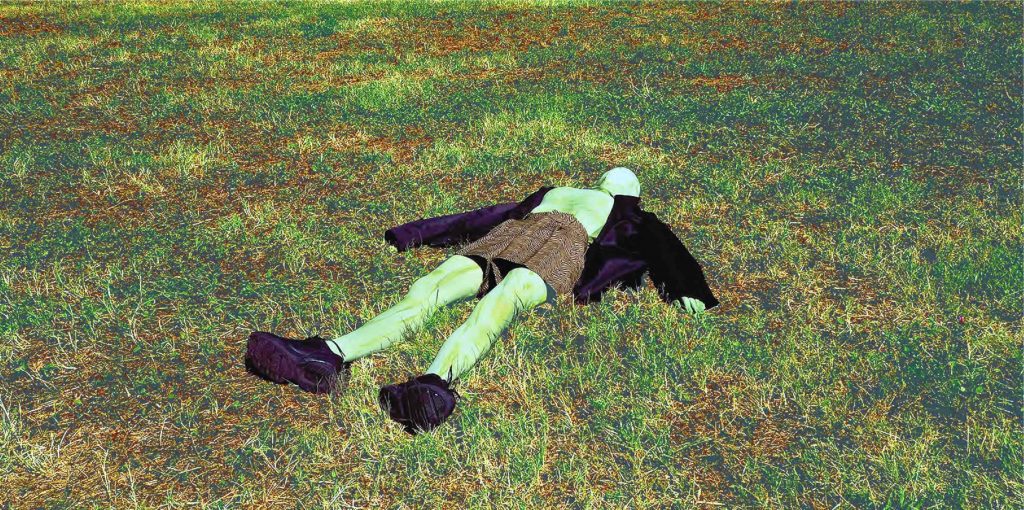

Common features are also the choice of the set (the Syrian Desert) and the typing of characters that while it polarizes the two identities of victims and perpetrator, making them instantly recognizable, on the other hand cancels the features, which distinguish the personalities acting on two aspects that are fundamental:

1) clothing (orange for the victims, in a clear allusion to the prisoners of Guantanamo and Abu Ghraib, and black for the executioner);

2) the behavioral expression (the psychology of victim and victimizer are flattened, and in the first ones they miss what O. Ponte di Pino has called “the excess of the body”: in other words, those sentenced to death will show apathetic, not rebel or not ready to escape, as if they indeed seem to collaborate).

Finally, to standardize the series helps even the general structure of the narratological sequences: each video normally starts from discursive brackets, made of recriminations and threats against the Western nations fighting the Islamic State; it follows the crucial time of execution of the offender, with the consequent exposure of the body without the neck; finally, it closes the admonition of the executioner, who reveals the identity of the next victim and puts his or her fate in the hands of the enemy nations.

We deduce the serial aspect of these movies in some specific linguistic formulas: “I’m back, Obama” is the debut phrase with which Jihadi John appears in the second episode of this series (video-execution of Steven Sotloff) and even more emblematic is the formula that he uses, always in reference to Sotloff but at end of the first movie, after killing James Foley: “the life of this American citizen, Obama, depends on your next decision.”

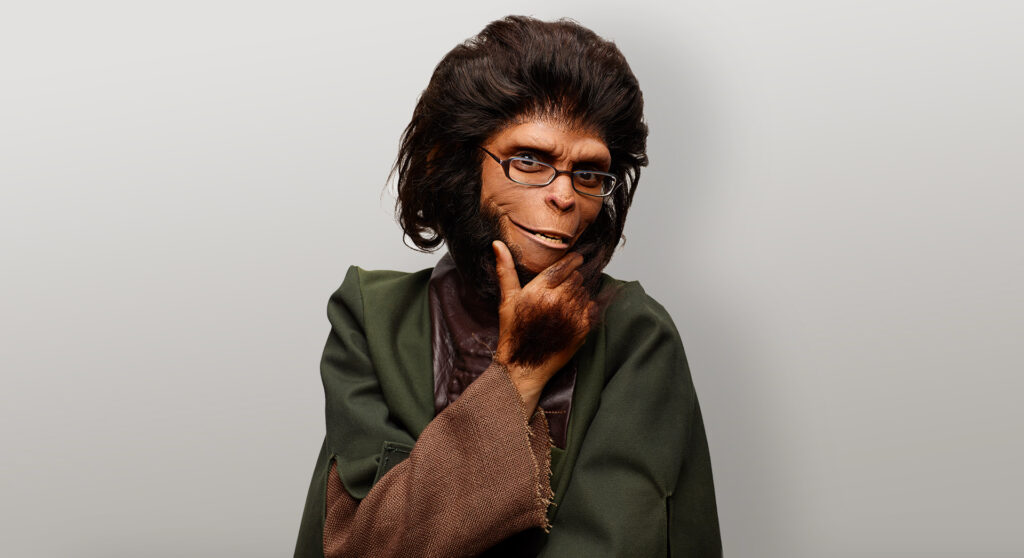

In these videos, all that remains of Mohammed Emwazi is attached and crystallized in the monolithic character of Jihadi John, who in turn is presented to us as the embodiment, transposed into reality, of that system of values and of those codes of expression that distinguish the villains of Western cinema. Everything, from the attitude until the Rambo-like knife with the slightly curved blade that recalls, as noted by Ballardini, “the sword, a symbol of Muslim warriors” (B. Ballardini, ISIS®. The marketing of the Apocalypse, Baldini & Castoldi, Milano 2015 ), frame the character within a stereotype to which he cannot escape. Once again, we are witnessing a bad smell vaguely of trivial.

However, in the bigger picture of terrorist communications strategies, these videos show, as mentioned, a significant renewal in the methods and instruments. Of the video-announcements of VHS Al Qaeda, with grainy images, the time-shifted audio, the fixed frame and a ‘lucky’ set, nothing is left. To the ugly middle-aged man who ranted against the camera, the IS has opposed the triumphalist image of a young hero (or anti-hero) seductive and cool, and although the coolness belongs to the subsequent video characters and not specifically to Jihadi John, we are always able to see, in one of the last video, that he is the protagonist, the harbingers of this general aesthetic care that will take shape more and more like the styling of the ‘film’ of jihad. The video in question is that of the execution of 21 Syrian soldiers near Dabiq, near the Turkish border.

The static shots of the previous videos are here replaced by dynamic shots, working in postproduction with effects and slow speed motion that increase the suspense, winking to the US action movie. The action begins with the procession of the condemned, escorted by his jailers that entered the scene with the military uniforms and face uncovered. A character dressed in black, who we immediately identify with Jihadi John, opens the long line. In turn, each militiaman wielding a knife taken from a box – a prop which gives greater solemnity to the sacrifice -, accompanied by a soundtrack (the nasheed) disturbed by metallic sounds of unsheathed knives. While Jihadi John turns his tirade to the United States, other militants are posing in front of the room, with a squad-like attitude. There follows a waiting time of about a minute, made up of silences and narrowing of the field on the faces of the victims and resigned on the hand of an impatient militiaman shaking the knife between his fingers. The effect reaches its climax in the final moment of the execution: the blood that flows from everywhere soaking the ground, save improbably the uniforms of the militiamen, remained untouched in the final scene showing the bodies of the victims. More than before the testimony of a sacrifice, we are facing one of its staging, whose reality effect is obtained by following the principles, modelled on the Western paradigm of representation and fiction.

The death of Mohammed Emwazi – which took place on November 12, 2015 – will not subtract to the common Western imagination the character of Jihadi John, that indeed we will fix even more when, in early January 2016, it will be spread by the Western mainstream media the news of an heir of Jihadi John (and not of Emwazi, mind you), in reference to the video-performing 5 alleged British spies.

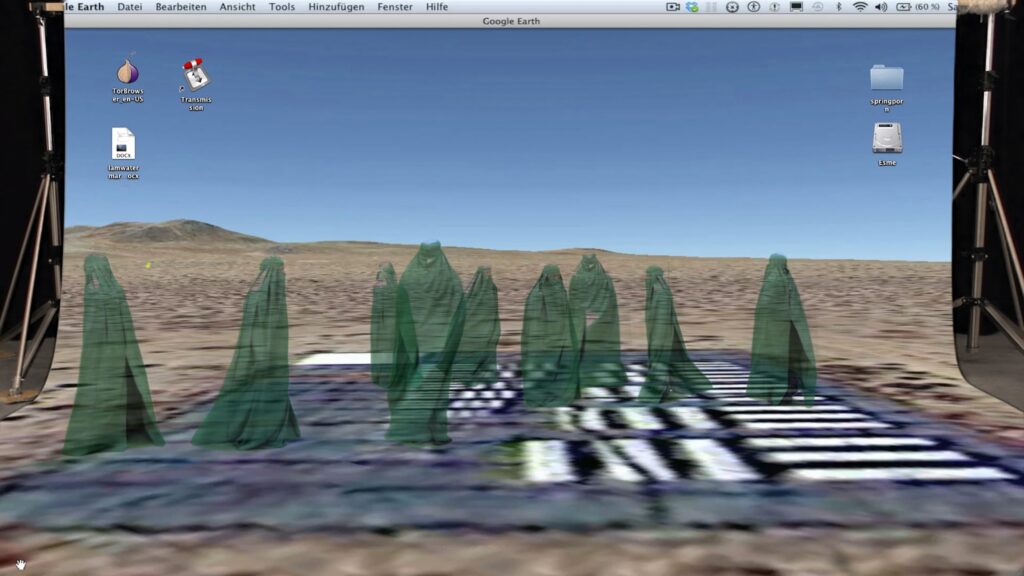

In the following movies to those that make up the saga of Jihadi John, the ties with the West mainstream culture will increasingly be obvious, and the self-congratulatory image with which the IS is always present will hold up the world more of a rich system of Anglo-American references, including cinema, music and video games. Following a mechanism that could be called ‘replacement for appropriation’, the IS uses the symbols of our mainstream culture to place them in a new context, making them their own, and using them as a propaganda weapon.

Harverst of the Spies #1 #2 #3

Three films, made between May and October 2015, show the executions of some alleged spies. Starting from the title, the videos define a trilogy, which reveals, within each chapter, precise serial characters.

First, each performance is preceded by an interview with the victim, which seems to mimic, thanks to the work of post-production, live-action cut-scenes of a video game, the narrative sequence in which we obtain information on the identity of a character and the story. At the beginning of the interview, it follows an excited moment of action, which may be held in the shadow of an industrial building, or in the countryside. The militiamen are moving on powerful cars, prominently the Toyota brand as in popular television commercials, flaunting a gangster attitude that recalls (unknowingly making a parody of) the hip-hop culture. As their executioners, the victims are here typed, according to schemes that have been already run: on them the usual orange uniform groups them to the point of depersonalizing them, wrists and ankles are tied to mark their state of helplessness, and posture kneeling indicates their full submission. The suspense is obtained as in a book, with a sequence of close-ups on the faces and weapons present in the scene, until the key moment in which the victim, with a gunshot or a large blade, is killed.

With respect to the previous saga, among the new narrative devices, it is interesting to note that, at the beginning of the third episode, there is an anticipation of what one is going to see a little later: it is a case of prolepsis (or flash-forward), emphasized by night effect, in which is prefigured the instant of shooting of four spies, which will be repeated, at the end of the movie, three times (a succession of three locations: front, side, and once again front, but with a sepia filter), ending with the final shot of an amphibious dipped in blood.

The strong symbolic connotations of a similar offense – the murderer who tramples on the blood of its victims – is explained by the realization of the research on the part of the IS, of the most striking and spectacular image that inevitably passes through the humiliation and annihilation of the body. By making a spectacle of death, the IS coded, making it mainstream, the kind of legendary snuff movie. In each video it does not matter much that the victim dies, but how it dies: a striking Libyan coast was the backdrop to the beheading of 21 Coptic Christians; a Jordanian pilot, kept locked in a cage, died devoured by flames after a long agony, while four hostages in a cage too, were lowered in the bottom of a swimming pool to be taken during the drowning; a man was killed crushed by a tank, another after being dragged along the tarmac by a van; on a hill, ten suspected spies have been blown up unleashing a rain of human remains, while the prisoners were on a swing, with their head covered, ready to be burned alive.

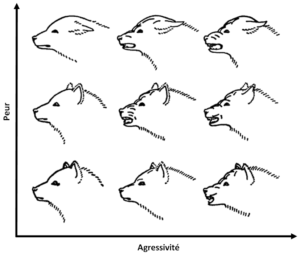

The vast repertoire of homicidal in the IS mode is therefore summed up in a single common denominator that provides for the dehumanization of the victim, reduced to inert object of a performance made possible by cutting-edge technological equipment and an extensive capacity of transmission offered by the new media. With “dehumanization” is meant, as explained by C. Volpato, “the negation of humanity, a process that introduces an asymmetry between those who enjoy the quality prototypical human and those who are considered deficient.” Dehumanize the victim therefore means denying his of her identity, subtracting the properties that define him or her as a person.

To the Sons of Jews

The video, of about 14 minutes, and dating back to December 3, 2015, begins with a sequence of images of the two targets that this time the IS intends to strike: Israel and its Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu. With a kind of mise en abyme, we observe a jihadist militia – whose face is framed, but this is probably a kid – insert on Facebook the video-execution, which we are going to see in a moment. Finished the buffering, the video can begin. Now we are catapulted in the governorate of Deir el-Zor. A class of boys, not more than ten or twelve, is intent on reading and studying the Koran in a desert background. An adult is their tutor and trainer, accompanying them in the reading of the sacred text, and training them to martial arts. As a test of loyalty towards the Caliphate, six young students are chosen to pass a test. The exam consists in the search and subsequent killing of six suspected spies held captive among the ancient ruins of the castle of al-Rahba. After some fascinating aerial shots of the stronghold, the mission of the young warriors starts, and the setting takes on the contours of a fantastic game, with a TPS (Third Person Shooter-visual action) and the suspense and anticipation climate of a Reverse Survival Horror. Walking through the dense, dark array of passages and tunnels, each one goes looking for his goal. The victims are disarmed and rendered entirely harmless: they have their wrists and ankles tied. The places where they hide them have a strong symbolic value: they are cramped, dark, small cavities difficult to access, a whole underground world to which belong rats, insects and, of course, the dead. The time when the perpetrator meets his victim is marked by an analepsis: to the main scene a short video is superimposed, shot earlier, when the victim reveals his identity. There is no escape for the prisoners, which are killed one by one, represented in their last moments of life in a state of semi-consciousness punctuated by gasps. Completed the mission, each militiaman goes back to where he started, and passes the baton (gun and balaclava) to the next upcoming murder. The manhunt is reopened.

This pattern is reflected on the entire narrative, except for the epilogue, in which there is the introduction of a variant: the death for a firearm is in fact replaced here by that for cutting weapon. Shouting “Allah Akbar”, a kid whose age proves even less than its younger counterparts, cuts in slow motion the throat of his victim, with a direct physical contact between the two that makes it even a more gruesome scene. The youngest warrior of the IS knows also how to be the most cruel and brutal murderer.

In this series of video performances what is to be celebrated is the triumph of death. In them we can see the little sense of attachment to life that characterizes the jihadist and distances himself from our Western culture, where the concept of existence is traditionally sacred and inviolable. However, on a closer look at them as a whole, the bloody images of these videos are dimidiate images of pain, where one can earn a rapid erosion of the sense of reality. The IS has accustomed us to the horror in HD, putting us in front of the linguistic codes that in our society are actually fictitious (precisely the cinema, the video games, etc.). Its sweetened and compelling images are ribs of our common Western imagination, and a mechanism that can appear perverse mortifies the victims as men in order to satisfy the viewers. As noted by O. Ponte di Pino, “to choose the most spectacular punishment, the IS adopts the same method used by film producers, and especially by the fan fiction authors: understanding the expectations of the public, asking the viewers’ help to write the ending of the story.”

The more the image is likely, the greater the shock. One element that most distinguishes the IS images from those of Auschwitz or Abu Ghraib is undoubtedly intentionality. The latter are considered as historical images, creating a scandal in the audience when it becomes conscious of having in its hands something that was not originally intended to itself. We are indignant in the face of the photographs of the dehumanized victims of Abu Ghraib, but before the video of the IS is inevitable to be educated to a sense of bitter disbelief. The horror jihadist propaganda hopelessly passes for the desensitization of the viewer. As claimed by E. Ferrari, “if the photograph has a consubstantial relationship with reality, prolonged exposure to photographs results in a de-realization experience of the world that diminishes our ability to interact with it. The usual vision of the horrible numbs us and paralyzes us: used to seeing the horrible in the image we no longer know how to react to it in reality.”

One of the most frightening effects of this gigantic mystifying and self-representative of the actual narrative is precisely the gradual habituation it generates in the viewer. The IS, in order to exist, requires that actors and audience of its propaganda to oscillate between a condition of apathy and an unrelenting state of inertia. Its strength lies in making us some sort of stones with our eyes glued to the screens, as an authentic and revived modern world Medusa, to know what will happen in the next episode.

More on Magazine & Editions

Magazine , MORIRE – Part II

Lo spettacolo della morte

È giusto morire sul grande schermo? Dal dibattito critico francese degli anni Cinquanta e Sessanta al cinema di Brian De Palma e Pippo Delbono.

Magazine , MORIRE – Part I

American way of death. La morte e il lutto in Occidente

Pornografia della morte e morte capovolta, da Gorer ad Ariès. L'«American way of death» tra tanatologia e giornalismo d'assalto.

Editions

Metadata Galaxies

Guida sul rapporto uomo-macchina, tra innovazioni tecnologiche e cambiamenti della società

Editions

Printed edition

Assedio e mobilità come modi per stare al mondo: le prime ricerche di KABUL in edizione limitata.

More on Digital Library & Projects

Digital Library

La Mia Morte

Un racconto polifonico degli ultimi istanti di vita di Pier Paolo Pasolini.

Digital Library

Superdiversità su Internet: un caso dalla Cina

MC Liangliang e il super-vernacolare globale dell’hip hop di Internet.

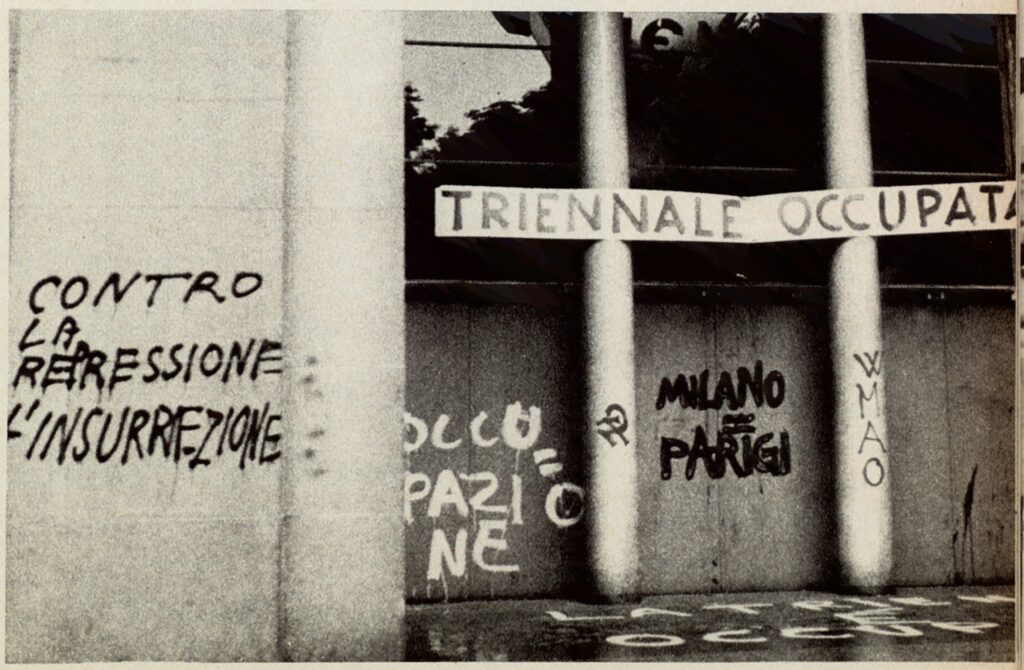

Magazine , PEOPLE - Part I

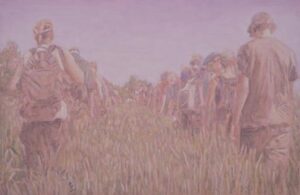

Una rilettura critica del 1968

Il 1968 oggi: eredità storiche, politiche e sociali all’interno di scuola, cultura e arte. Un testo di Loredana Parmesani sulle riviste e le esperienze di critica militante.

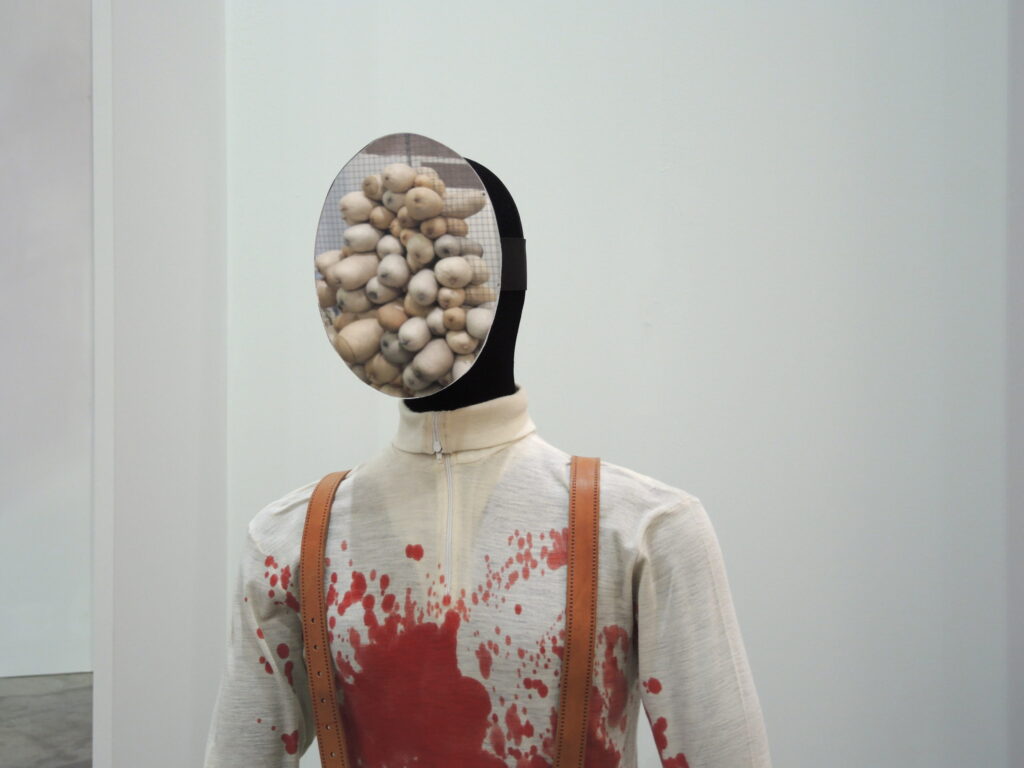

Magazine , PEOPLE - Part I

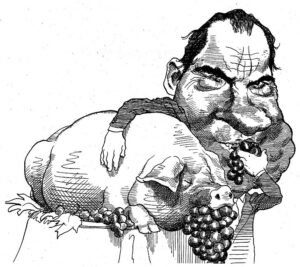

La grande abbuffata: dall’Ultima cena al food porn (#artissimalive)

The Edit Dinner Prize: il rapporto tra arte e cibo tra storia dell'arte e ossessioni culinarie contemporanee.

Iscriviti alla Newsletter

"Information is power. But like all power, there are those who want to keep it for themselves. But sharing isn’t immoral – it’s a moral imperative” (Aaron Swartz)

-

Dario Alì è Responsabile didattico per Formazione su Misura (Mondadori Education – Rizzoli Education) e Direttore editoriale di KABUL magazine. Dopo aver conseguito una laurea magistrale in Filologia della letteratura italiana, partecipa a CAMPO (Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo) e ottiene un master in Editoria cartacea e digitale presso l’Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore. È autore, per De Agostini, di due volumi biografici su Torquato Tasso e Lorenzo Valla. Attualmente vive e lavora a Milano.

B. Ballardini, ISIS®. Il marketing dell’Apocalisse, Baldini&Castoldi, Milano 2015.

N. Mirzoeff, Introduzione alla cultura visuale, Booklet, Milano 2005.

C. Volpato, Deumanizzazione. Come si legittima la violenza, Laterza, Bari 2011.

SITOGRAPHY

G. Calamari, ISIS e l’estetica del terrore, «Gli Stati Generali», 10 Feb. 2015.

F. D’Asaro, Lo spettacolo dei video dell’ISIS, «Dude Mag», 22 Apr. 2015.

E. Ferrari, S. Sontag. Sulla fotografia. Realtà e immagine nella nostra società, «Itinera».

M. Hussain, Grand Theft Auto: ISIS?, «The Intercept», 17 Sept. 2014.

J. C. Kang, Isis’s Call of Duty, «The New Yorker», 18 Sept. 2014.

F. Pintarelli, Quando ISIS incontra Call of Duty, «Prismo», 11 Apr. 2016.

O. Ponte Di Pino, Il Grande Vecchio ovvero La guerra delle immagini, «Doppiozero», 7 Sept. 2015.

S. Rose, The Isis propaganda war: a hi-tech media jihad, «The Guardian», 7 Oct. 2014.

C. Volpato, La negazione dell’umanità: i percorsi della deumanizzazione, «Rivista internazionale di filosofia e psicologia», 2012.

KABUL è una rivista di arti e culture contemporanee (KABUL magazine), una casa editrice indipendente (KABUL editions), un archivio digitale gratuito di traduzioni (KABUL digital library), un’associazione culturale no profit (KABUL projects). KABUL opera dal 2016 per la promozione della cultura contemporanea in Italia. Insieme a critici, docenti universitari e operatori del settore, si occupa di divulgare argomenti e ricerche centrali nell’attuale dibattito artistico e culturale internazionale.