reserve, 2018: A work composed for the Heimatmuseum Reinickendorf, a small museum on the northern perimeter of Berlin, as part of an exhibition entitled “Interventions”. This project was censored by the museum, and was never exhibited, despite the support of the project’s curator (Dr. Lily Fürstenow-Khositashvili). The intended work consisted of a video, letter, and a proposed extraction.

reserve, 2018: A work composed for the Heimatmuseum Reinickendorf, a small museum on the northern perimeter of Berlin, as part of an exhibition entitled “Interventions”. This project was censored by the museum, and was never exhibited, despite the support of the project’s curator (Dr. Lily Fürstenow-Khositashvili). The intended work consisted of a video, letter, and a proposed extraction.

In the video, the museum director Dr. Cornelia Gerner handles items from the museum collection that are also artefacts of Nazi presence in Reinickendorf. The camera focuses on Dr. Gerner’s hands as she caresses and unwraps each artefact, describing how the museum acquired each item, and for what reason the museum feels these items contribute to its collection.

The letter, sent to the museum direction shortly after the video was recorded, criticized the museum’s claim to represent the current and hisorical inhabitants of the district, given its collection of Nazi artefacts, and especially with regard to the absence of artefacts of Jewish presence, aside from crude reproductions of markers of their death. In it, the artist requested the museum’s participation in a reciprocal form of reparation: the withdrawal or deaccession of one of the fascist artefacts from their collection, in order to deny it the respect of preservation, and to reduce the weight of these objects in the museum’s holdings. The museum refused this request, and moreover refused to permit the letter to be exhibited. Further, they refused to exhibit the video without modifications according to their determination.

Opening the website of Canadian born and Berlin based artist Joshua Schwebel’s website, one has the impression of staring at the summary of an institutional critique book. The side bar is populated with all the subjects of the artworld, together with words that indicate acts of privation or displacement. The artist’s work concentrates in fact on continuously stressing the institutional machine that hides behind the artworks, through actions that play with power relations, bureaucratic dynamics and with the invisible subjects of art.

In Popularity, 2012, every day, for 5 weeks, 35 random people were paid to enter the same exhibition space. At the end of the operation, all of Canada’s exhibition spaces, who rely on public funding based on the number of visitors entering the space, received a card explaining the project without revealing the name of the space in which the action had taken place. For Subsidy, 2015, the unpaid interns of the Künstlerhaus Bethanien in Berlin received a stipend to keep doing whatever they were already doing. Evictions, 2018, had the employees of the Laznia CCA residency in Gdansk move their offices in a Center for Integration, while their desks where taken over by a grassroots group that works with youth from the working-class neighborhood of Nowy Port.

Those are just three examples of the displacements operated by Schwebel in the institutions that hosted him. The artist is always concerned with the issues of the place in which he is working and, has he moves resources, objects, and people, he tries to undermine the foundations of the institutional structure, in order to face it and eventually put it under discussion. The tools used by Schwebels for his operations are those of bureaucracy, such as letters, receipts, contracts, money and employees. What is left out is the actual object-artwork with which the public is usually relating. The disappearance of objects, explains Schwebels in the interview, is actually able to highlight the relations that are based upon them, and brings both the public and those who are involved in the action to a confrontation with the invisible side of the art system. The artist is thus inspecting the dualism of the artworld which, despite having to repeat neoliberal and capitalistic patterns taken from bureaucratic, political and economic structures, hopes to preserve its anti-institutional soul.

Saturday, April 6, Joshua Schwebel will present, at the project space Standards (Milan), the live performance Second Summons (Seconda Convocazione), curated by Michele Lori and Sara Castiglioni, during which the artist will try to play out the criticalities and fictions of the bureaucratic system to which a no-profit reality has to submit in order to operate in the Italian artistic context: a sort of confession to the public that will oblige the founders of the space to reveal what usually remains hidden. The performance will be followed by Sonniloquio per restare, a project curated by Michele Lori, Silvia Costa, Joshua Schwebel and Sara Castiglioni, that will consist of a series of readings extending the themes dear to Schwebel, accompanied by sound compositions by artist Valerio Maiolo.

Elena D’Angelo: I found your relationship with objects to be quite interesting: you almost never produce them, if not in the form of letters or displays, or more rarely as drawn copies of other objects. Still, they are very present in your work as things to be moved or taken. How do you select the things you want to displace? What do you think is an object’s role in redefining historical authority?

subsidy, 2015: An intervention enacted during a year-long residency at the Künstlerhaus Bethanien, Berlin. The artist used the complete amount available for my exhibition budget (€3.000) to compensate the normally unpaid interns working in the institution’s administrative offices. A total of seven interns were paid an honorary fee from my budget for the “performance of administrative duties” in the KB office.

subsidy, 2015: An intervention enacted during a year-long residency at the Künstlerhaus Bethanien, Berlin. The artist used the complete amount available for my exhibition budget (€3.000) to compensate the normally unpaid interns working in the institution’s administrative offices. A total of seven interns were paid an honorary fee from my budget for the “performance of administrative duties” in the KB office.

Joshua Schwebel: Bluntly put. I am not interested in objects in themselves. Foremost, I am interested in relationships, and how they are structured. This is a political and not an aesthetic concern. I often focus on relationships within art institutions, because those relationships are formalized, and as such, are a cultural product in themselves. Because the encounter with art is most often mediated through institutionalized structures that set the conditions for how we imagine and recognize what art can be, these structures should be examined and questioned, rather than taken as a given.

Authority, power, and value are expressed and enforced through institutions’ hierarchical relationships, which are always already normalized to the point of social invisibility. I try, in my work, to observe these structures of institutionalized power, and to examine, when necessary, and if possible, any imbalances that I notice.

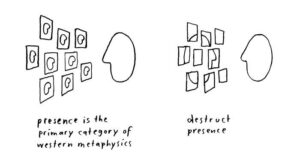

If a particular object expresses or crystallizes relationships of authority, power, or value in the defined realm of my project, then that object is interesting. I examine the conditions by which that object has come to be where or what it is, and then ask myself: if I remove that object from the structure or field of meaning in which it operates, what happens? What about if I double it? Or make a counterfeit copy of it? I conduct these experiments with or around the object. However, the reactions that these shifts might generate are what is of interest to me, not the object in and of itself.

Elena D’Angelo: Most of your works seem to operate a displacement either of objects or bodies, of workforce or intention. If this action had a sort of humorous and ironic feel at the beginning of your practice, with time this operation became more critical and unsettling. What do you think is the effect of a change in context? Do you see a political value in the act of removing and misplacing something or someone?

Joshua Schwebel: In an art exhibition context, the object is usually the only thing the public sees. As I said, the object in itself is not interesting to me, but, the object on display and holding the place of ‘art’ distracts us from a network of embedded expectations, power relations, and ambitions. By taking the object away I want to make visible everything at play around and behind it.

Since my interest is in disclosing relationships and the entanglements of political interests that those relationships contain, I focus within the institution itself, to what is already internal to any organized structure. Within these structures the roles of people are fit into heirarchies, people have more or less value, authority, legitimacy, etc. (this is not neutral). In other words, institutional structures always already treat people like objects.

I employ artistic techniques of material reconfiguration, including redistribution, displacement, infiltration, extractions, or insertions. These actions are essentially my artistic work, although they are barely visible to the visiting public since they effect the administrative engine of the institution by imposing a supplemental artistic function, or dysfunction, onto the administrative tasks of operating the institution.

Often the outcome of my intervention is internal political conflict, which exposes the institution to itself. Art institutions are particularly interesting to me because they claim loyalty to art. This is, at its core, an impossible and therefore dishonest mandate, because art is fundamentally anti-institutional, or at the very least the neo-liberal and capitalist values that the institution must incorporate in order to sustain itself (under most public or private funding systems), are antithetical to artistic values.

Through my work I try to split these loyalties, and to make their inherent contradictions visible. In the face of my proposed intervention, an arts administrator’s dual loyalties – to art’s exceptionality or institutional order – are dissected. The disagreements, refusals, or acceptances of my proposed interventions reveal the (power) structures of institutionalized art, and the specific configuration of the institution in question. I archive the correspondence and negotiations involved in producing the work, which become the primary material for what I exhibit to the public.

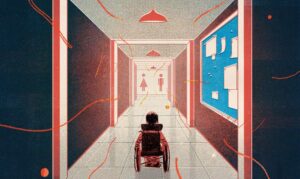

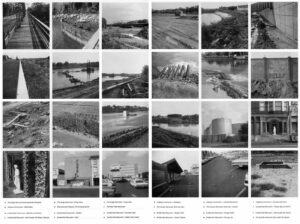

evictions, 2016-2018: Evictions was realized in the context of a long-term residency thematized around art in public space (5 months, distributed over 3 years). The residency site is located in Nowy Port: a neglected, working-class neighbourhood of Gdansk, Poland, which has been subjected to city-led revitalization since 2013. Laznia contemporary art centre’s placement in this district was a major element of the city’s revitalization project. The artist’s project implemented a three-way exchange of office spaces between Laznia and two nearby social-service organizations. The exchange took place over the full month of September 2018. Six cultural workers (curators and educators) employed by Laznia moved out of the building to work at desks in shared offices at CIS: the Centre for Integration, an organization within walking distance of the arts centre that supports local impoverished and at-risk clients. The vacated offices within Laznia were occupied by Youth 180°, a grassroots group that works with local youth. At the time of the project, Youth 180° did not have their own workspace, and were able to use Laznia for workshops, counselling, and office-space; temporarily re-signifying the contemporary art building by bringing their clients into the arts centre who would otherwise not enter.

evictions, 2016-2018: Evictions was realized in the context of a long-term residency thematized around art in public space (5 months, distributed over 3 years). The residency site is located in Nowy Port: a neglected, working-class neighbourhood of Gdansk, Poland, which has been subjected to city-led revitalization since 2013. Laznia contemporary art centre’s placement in this district was a major element of the city’s revitalization project. The artist’s project implemented a three-way exchange of office spaces between Laznia and two nearby social-service organizations. The exchange took place over the full month of September 2018. Six cultural workers (curators and educators) employed by Laznia moved out of the building to work at desks in shared offices at CIS: the Centre for Integration, an organization within walking distance of the arts centre that supports local impoverished and at-risk clients. The vacated offices within Laznia were occupied by Youth 180°, a grassroots group that works with local youth. At the time of the project, Youth 180° did not have their own workspace, and were able to use Laznia for workshops, counselling, and office-space; temporarily re-signifying the contemporary art building by bringing their clients into the arts centre who would otherwise not enter.

Elena D’Angelo: There are at least two occasions in which your projects have, from my understanding, made institutional workers feel threatened on a personal level. If in the case of your residency at Künstlerhaus Bethanien in Berlin the threat was finally understood as a critique to the system in general, your proposal for the Museum Reinickendorf was put to an end by the museum direction. Why do you think it is that institutional characters feel personally threatened when they encounter a project criticizing not them, but the institution they work for? Why is it that the art system, which should by now feel comfortable with institutional critique, is still incapable of looking at itself with a critical eye?

Joshua Schwebel: Power is not self-evident. It is concealed and distributed. Power is also invested in maintaining stasis and invisibility. Embedded structures of power conceal the violence or force that were instrumentalized towards their acquisition. Any efforts to disclose or shift power structures is seen as an attack.

In the context of my residency at Künstlerhaus Bethanien, my project was to use funding I had received from the Canadian province of Québec to compensate the interns who were working in the offices of the Bethanien residency, and whose work was otherwise unpaid. This compensation was disbursed to the interns whose work occurred during the year of my residency. It is disappointing that the director of the residency saw this as cause to feel threatened. I exposed an abuse of power within the institution he directs. I exposed his willingness to uphold inequalities of power that are stagnant and pervasive throughout the art world. However, I did nothing to attack him personally or to make him feel unsafe.

Foucault states:

“The real political task in a society such as ours is to criticize the workings of institutions that appear to be both neutral and independent, to criticize and attack them in such a manner that the political violence that has always exercised itself obscurely through them will be unmasked, so that one can fight against them”.11Foucault-Chomsky debate.

People are often so invested in the structures of institutional power as given, that when I make the inherent inadequacy or hypocrisies of those structures visible, it provokes a defense of the institution. It makes me sad that people would rather rush to the defense of an unhealthy systemic situation than to recognize that it needs to be changed, and work together to make things better. Five years after my residency at the Künstlerhaus Bethanien, there are still unwaged interns working in the offices.

Elena D’Angelo: In many of your works there seems to be the necessity to engage with what happens on the edges of the artworld, be it through the position of interns, administrative workers, cultural mediators or of the public in general. Are you interested in putting under discussion the relationship between art practice and its public and workforce?

Joshua Schwebel: Yes.

Elena D’Angelo: The work you will present at standards begins with an analysis of the necessities and issues that are tied to non-profit cultural organizations to end with a reading of theoretical texts. Considering that most of your works relate very deeply to the issues of the environment in which they are presented, why did you chose this project for Milan in general and Standards in particular? Could you give us an anticipation of these references and of the reasons why you thought they connected to this particular environment?

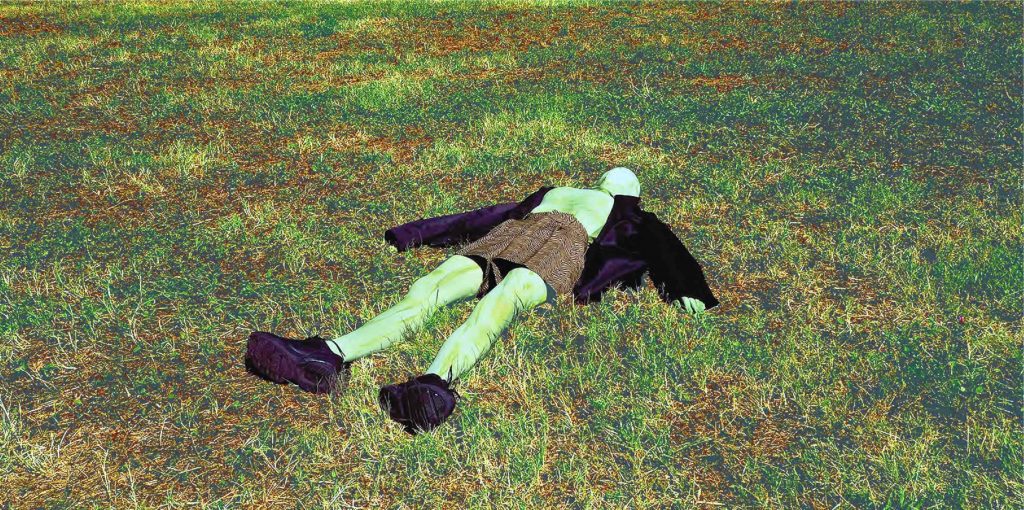

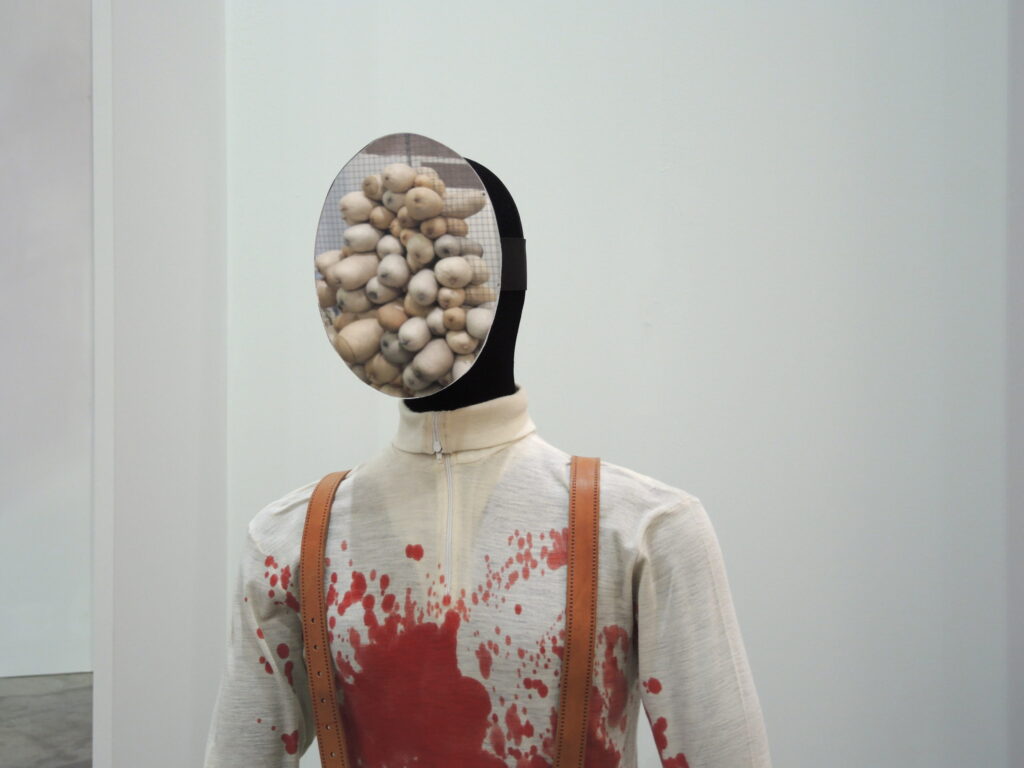

privation, 2016: Through a contractually defined agreement between the artist and art collector Jochen Kienzle, Schwebel was permitted 20 minutes unsupervised and alone in the collector’s home in order to remove a single object. The identity of this extracted object – one that is banal, and therefore unplaceable – is to perpetually remain a secret, concealed from both the collector and public knowledge. The extraction introduces an undetermined absence into the collector’s domestic space. The Kienzle art collection also acquired this intervention, in the form of an unspecifiable lack, as an artwork within its holdings.

privation, 2016: Through a contractually defined agreement between the artist and art collector Jochen Kienzle, Schwebel was permitted 20 minutes unsupervised and alone in the collector’s home in order to remove a single object. The identity of this extracted object – one that is banal, and therefore unplaceable – is to perpetually remain a secret, concealed from both the collector and public knowledge. The extraction introduces an undetermined absence into the collector’s domestic space. The Kienzle art collection also acquired this intervention, in the form of an unspecifiable lack, as an artwork within its holdings.

Joshua Schwebel: When I met with the people who created ‘Standards’, I was introduced to a young cultural association that is grappling with several intersecting issues around precarity, institutionalization, and the bureaucratic and administrative loopholes that they must negotiate to organize their events. In order to exist as an association and to receive public funding for the events they organize, Standards must adopt some recognizable institution-like structure. yet in order to avoid the pitfalls of institutionalization, namely rigid internal heirarchies, pre-determined exhibition or event cycles, etc., it seems important to discuss the extent to which they adopt these forms, and their benefits and detriments carefully and at length. The first part of the project will be a discussion that addresses these questions, while formally reflecting the institutional structure and the boundary between private and public space that it represents. The second part of the evening has been developed in collaboration with Standards organizers, and will be a sort of collective reading of some texts that have been influential for myself – and members of Standards will also contribute in kind. These will be texts that engage more deeply with the administration of art, the effects of bureaucratic regulation, and the ever-possible realm of the counterfeit.

popularity, 2012: Over the course of a single, five-week exhibition, the artist paid people to attend a gallery as counterfeit spectators in order to artificially inflate the popularity of the show. The action was executed without the knowledge or consent of the staff of the artist-run centre, or the artist whose exhibition was inexplicably popular. The thus-composed ‘art public’ of 35 people per day attended a single show every day for five weeks, standing in the gallery for a minimum of 10 minutes. In total almost 1,000 counterfeit visits were generated.

popularity, 2012: Over the course of a single, five-week exhibition, the artist paid people to attend a gallery as counterfeit spectators in order to artificially inflate the popularity of the show. The action was executed without the knowledge or consent of the staff of the artist-run centre, or the artist whose exhibition was inexplicably popular. The thus-composed ‘art public’ of 35 people per day attended a single show every day for five weeks, standing in the gallery for a minimum of 10 minutes. In total almost 1,000 counterfeit visits were generated.

Joshua Schwebel è artista concettuale canadese con sede a Berlino. Attraverso interventi artistici, il suo lavoro de-centra l’autorità istituzionale e rende visibili le strutture di potere e le gerarchie che risiedono nel sistema dell’arte.

More on Magazine & Editions

Magazine , ESCAPISMI - Part I

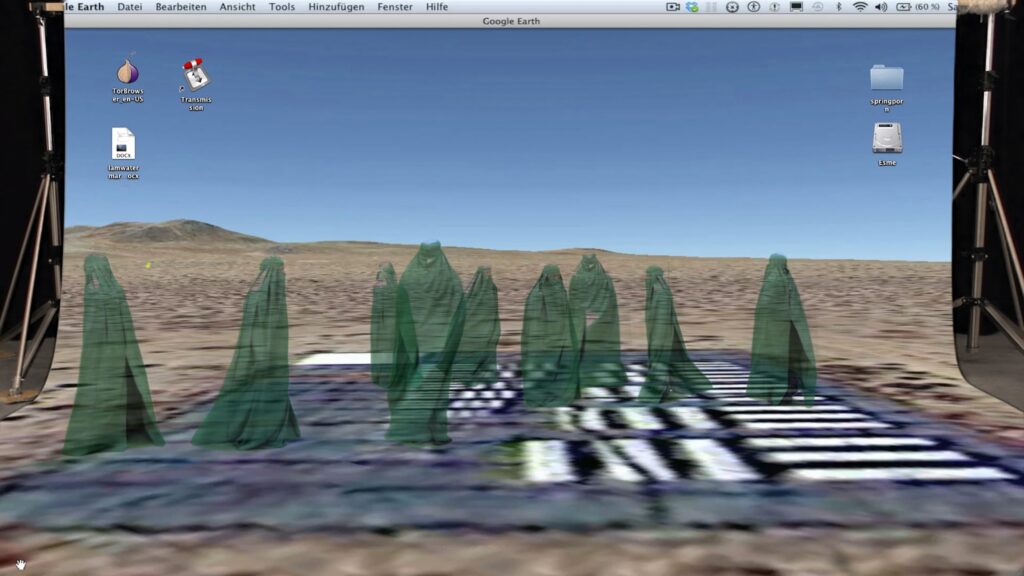

Sparire dentro un pixel

Pratiche di in-visibilità a partire da “How not to be seen: a fucking didactic educational.mov file”

Magazine , ESCAPISMI - Part I

Spettacolarizzazione del conflitto

Strategie di coping nell’epoca della necropolitica

Editions

Printed edition

Assedio e mobilità come modi per stare al mondo: le prime ricerche di KABUL in edizione limitata.

Editions

Utopia on now. Dalle avanguardie artistiche all'utopia del fallimento

Excursus teorico dalla definizione di utopia classica al suo fallimento e alla sua ridefinizione

More on Digital Library & Projects

Digital Library

Imitazione di un Sogno

Esplorazioni filosofiche e sensoriali tra sogno e realtà.

Digital Library

La tanatopolitica e il suicidio per mano della società

"Il tempo è finalmente scaduto... Non sono una brava persona, ho fatto cose cattive. Ho ucciso, e ora è tempo che mi uccida": su guerra e pandemia per disaffermare la biopolitica.

Projects

Le forme pop della didascalia

L’uso della didascalia nel contesto museale e la descrizione dell’immagine nell'epoca della cultura visiva: una riflessione scaturita dal secondo appuntamento di Q-RATED (Quadriennale di Roma).

Projects

Sconfiggere il populismo sovranista con il linguaggio esoterico dell’arte contemporanea e la collaborazione dei musei

Quali sono i diversi approcci adottati da curatori e direttori di musei per condurre un workshop nella propria istituzione? Una riflessione scaturita da Q-RATED, il programma di workshop organizzato da Quadriennale di Roma.

Iscriviti alla Newsletter

"Information is power. But like all power, there are those who want to keep it for themselves. But sharing isn’t immoral – it’s a moral imperative” (Aaron Swartz)

-

Elena D’Angelo (1990) is a freelance producer and copy editor. She holds a BA in Art history for the Milan State University and an MA in Visual Cultures and Curatorial Practices at the Brera Academy of Fine Arts. She has worked as a producer at Castello di Rivoli Museo d’Arte Contemporanea, having the chance to organize exhibitions and projects for artists such as Anri Sala, Hito Steyerl, Nalini Malani and Cécile B. Evans. She is currently collaborating with Mattatoio, Roma, and is a partner of the online video archive instudio.

KABUL è una rivista di arti e culture contemporanee (KABUL magazine), una casa editrice indipendente (KABUL editions), un archivio digitale gratuito di traduzioni (KABUL digital library), un’associazione culturale no profit (KABUL projects). KABUL opera dal 2016 per la promozione della cultura contemporanea in Italia. Insieme a critici, docenti universitari e operatori del settore, si occupa di divulgare argomenti e ricerche centrali nell’attuale dibattito artistico e culturale internazionale.