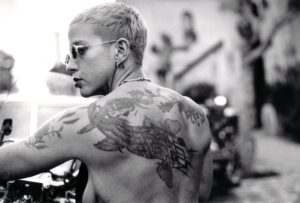

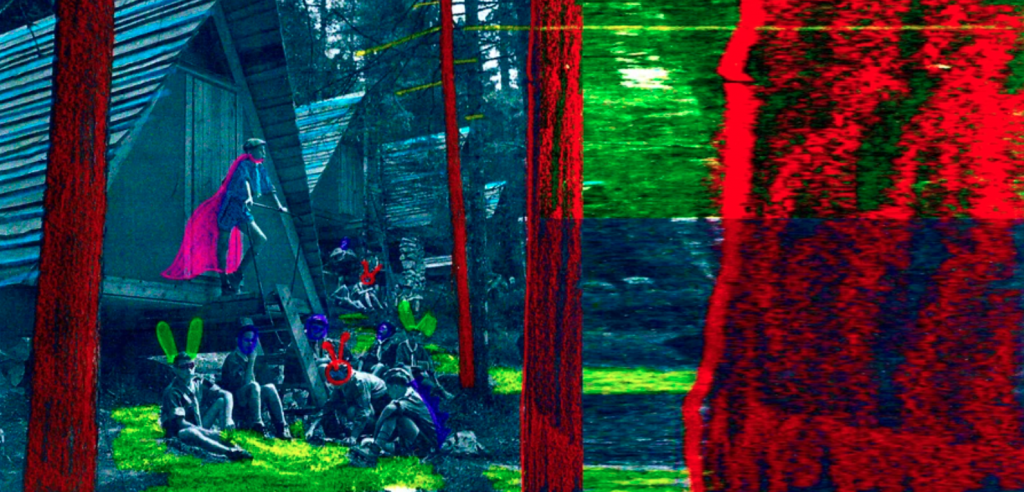

Born in Los Angeles in 1988, Martine Syms is one of the most interesting artists discussing current representations of blackness. Working primarily with moving images and performance, she creates films and installations in which the lives, gestures and possibilities of women of color are analyzed through a wide use of irony and popular culture. In the interview Syms discusses white privilege and its interpretation of her self-given definition of “cultural entrepreneur”, her relation with the public in exhibition spaces and her use of displays, narration and performativity. She also talks about one of her most recent works, an interactive “threat model” presented at Sadie Coles at the end of 2018, in which an avatar responded to the texts of the public with phrases that recall black culture and real life exchanges.. Her work has been shown, among others, at MoMA, NY, Sadie Coles, London and more recently at the Institute of Contemporary Art at Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond VA, and at Secession, Wienn.

AUTHOR: Elena D’Angelo, Caterina Molteni

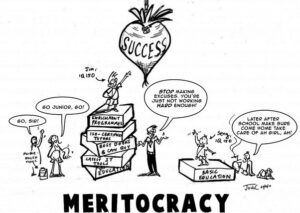

Elena D’Angelo, Caterina Molteni: We’ve been reading in a few of your statements and interviews that for quite a long time you’ve defined yourself as a “conceptual entrepreneur”. From the point of view of our European, and more specifically Italian context, the association of a business-tied term to an artistic practice is easily read as a sort of indulging attitude towards the neo-liberal economic model. Seeing your Lesson I though, it feels like there might me a wider spectrum behind this idea. How do you relate with this ambivalence? How can we conceive the idea of business as a way of emancipating ourselves from the model itself? Are you ever afraid that, in the end, even your business is bound to be absorbed?

Martine Syms: The fact that I’m still being asked this question after twelve years is shocking! I stopped using that term a while ago, but it won’t die. Why is that? It’s easy for people of privilege to see making money as dirty. If you don’t come from that background the idea that one could create a self-sufficient, sustainable, generative infrastructure driven by artistic practice is an urgent need. I am very influenced by the Black Panthers’ writing about economic self-reliance, mom and pop stores that perform multiple functions for underserved communities, and the autonomous culture of punk and hardcore. Given lack of resources, lack of public funding, and lack of familial wealth you’ll be shit outta luck without a business model. This is not a theoretical position for me. I am an artist. Perhaps I made a mistake years ago by talking about money with rich people. I don’t propose to be liberated. My participation in the art world is complicit, as is yours. We all must negotiate that for ourselves. I would like to be able to make art for a long time, hence my need for money.

ED/CM: Your work relates to many different forms of performativity. You have worked on singular gestures and on the way in which they are applied in daily life (Notes on Gesture, 2015). There’s also a lot of thought on the gulf between fiction and reality, as you put yourself in the position of the ‘unreliable narrator’ (A Pilot for a Show About Nowhere, 2015). All of this is always placed in a carefully conceived exhibition space, that often recalls a stage or a set, distancing itself from the canonical use of the white cube and inviting the public to have a performative attitude and to interact with the work. Even color becomes a tool to give a very specific impression. Do you think the moment of the exhibition can be a chance to criticize a certain way of conceiving the museum space? Can this performativity in the public, in the work itself and even in the structure of the exhibition be a tool for political action?

M. S.: I am more interested in the museum visitor than the museum space. I want them to have an immediate visceral and emotional reaction. My background is in film and I’ve always had this control fantasy. Sort of like the John Smith film The Girl with Chewing Gum. I think about everything that could happen in my space. I score it. It is part of the work. Obviously I am always surprised by people when they are actually in the space but that’s fun for me. Recently someone stole a piece of my work from a museum. It was the highest compliment.

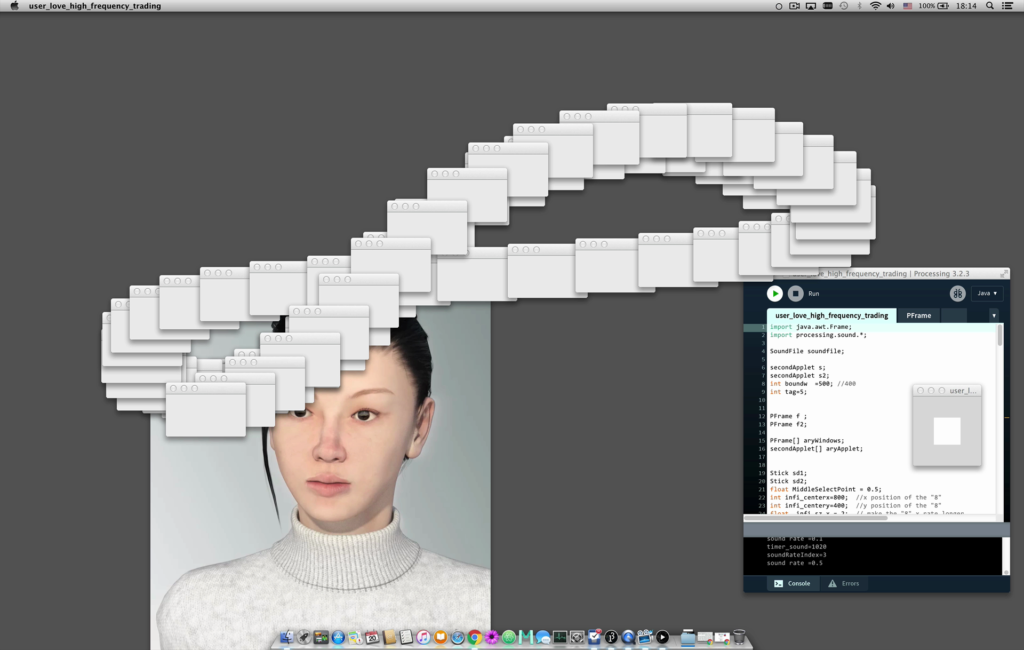

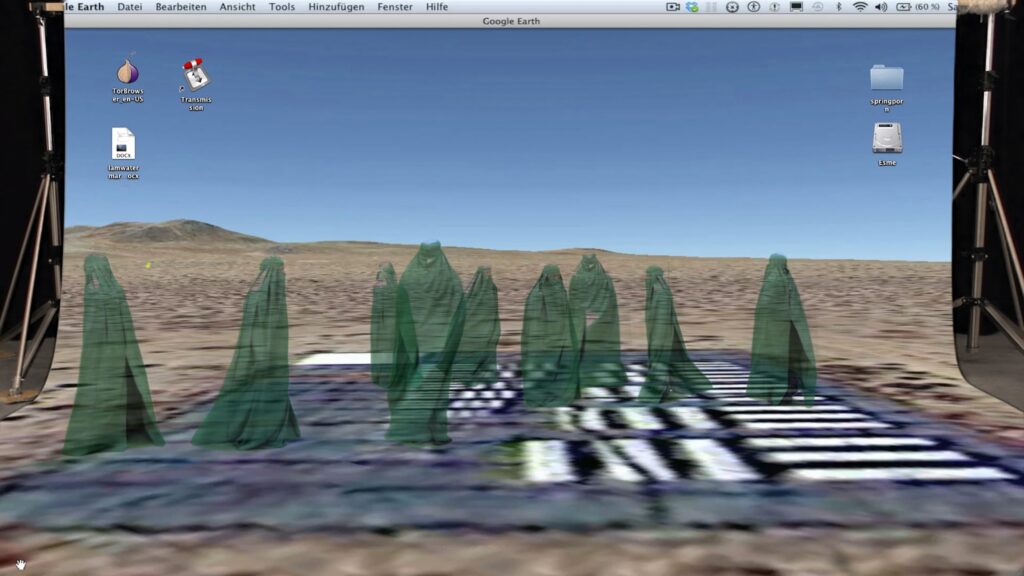

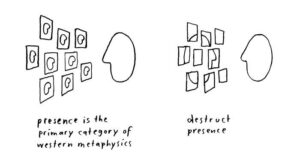

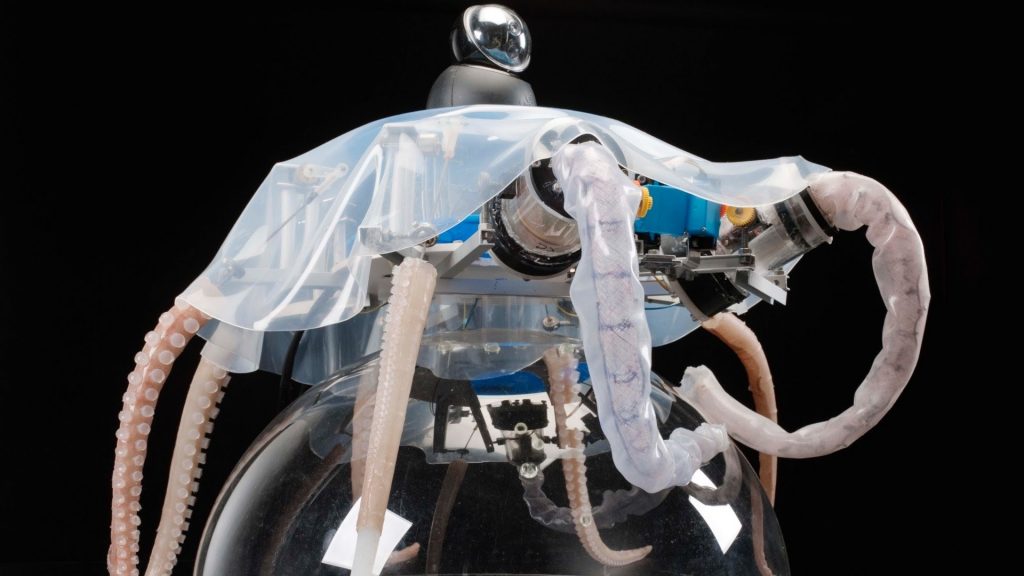

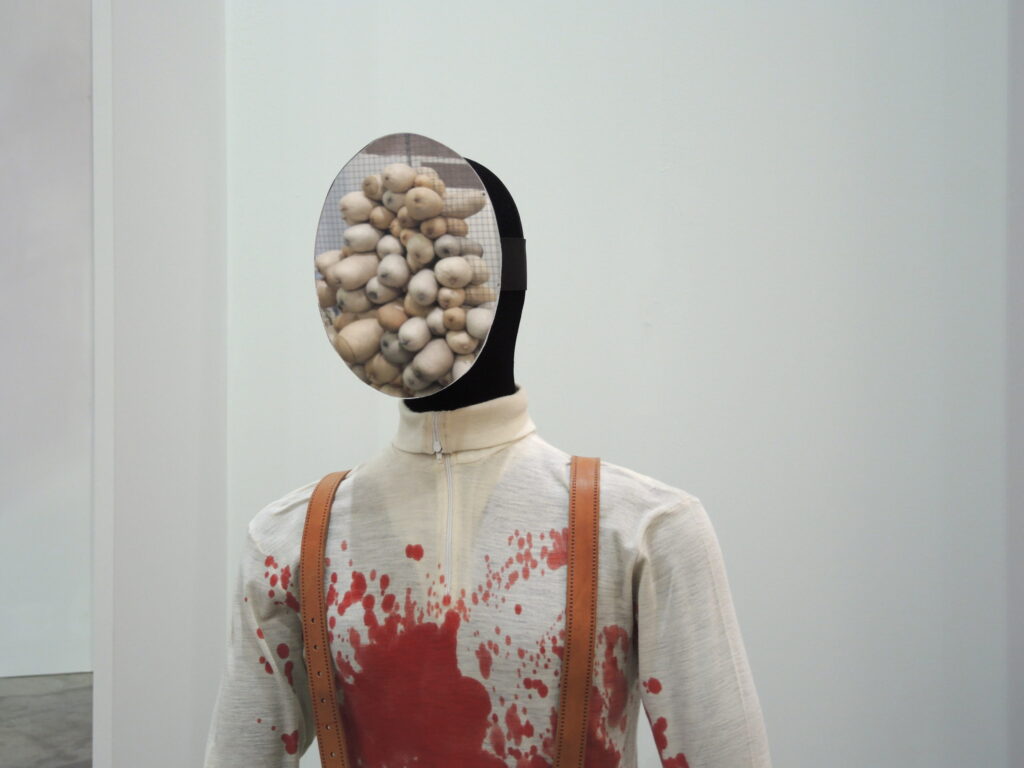

ED/CM: For your exhibition at Sadie Coles you decided to use your own avatar as a threat model that responded to texts sent by the audience. How did you get to the choice of using a threat model, a purely digital and technological system, to defend what seems to be the most authentic and fragile side of a person?

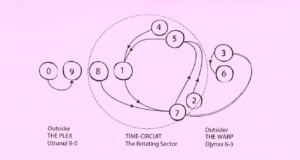

M. S.: Threat modeling is a process used by info security teams to determine the threats / vulnerabilities of your system. The process begins with a series of questions about values that reminded me of cognitive behavioral therapy. I was interested in that as a metaphor for psychoanalysis. Two ways of dealing with profound cultural anxiety. What’s curious to me about AI is how it calls into question the category of “human” and “consciousness.” These terms are fraught and have excluded blacks, women, other oppressed groups throughout history. I’m making a link between the two.

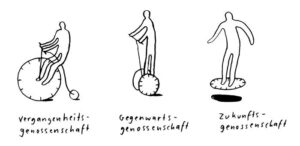

ED/CM: In your work, it’s possible to find a particular use of irony. In contrast to common memes that seem to promote a communication with pre-packaged masks made by ironic and conforming slogans, you bring irony back to be a spontaneous form of communication, often thanks to the use of a visceral and vernacular language. This irony also seems to become the “threat model” we were just speaking about, a tool to protect one’s own fragility, which however transpires in an even more effective way. Can the display of one’s own fragility and emotionality be a value today? Is it possible today to find a return to the search for conditions of authenticity and sincerity? Can it be traced back to a kind of reaction towards the neoliberal society based on the maximum efficiency of the individual?

M. S.: I like to think I use humor more than irony, but I am kind of a troll so touché. I am always 100% sincere. Everything on that wall is directly from my journal. Mythiccbeing was a way of thinking about inefficient machines. I loved Jennifer K. Alexander’s book the The Mantra of Efficiency: From Waterwheel to Social Control, in which she describes making the machine “thick enough to see.” My working title was “make it thicc,” which meant making it visible, but also making it black.

ED/CM: We never had the chance to see your work in person, but we started getting really excited about it as we were researching the history of Afrofuturism, and stumbled upon your 2013 Mundane Afrofuturist Manifesto on Rhizome. We were particularly taken by the very realistic, and yet scary, vision of a future in which “we only have ourselves and this planet”, without any mean for escaping. The future you describe however, is everything but dystopian: it is mainly real and tangible, and has in itself the possibility of actual, and not magical, change. So did your idea on what we should do with this world change in five years? Should we still play by the rules of your manifesto, or should we burn it and move on?