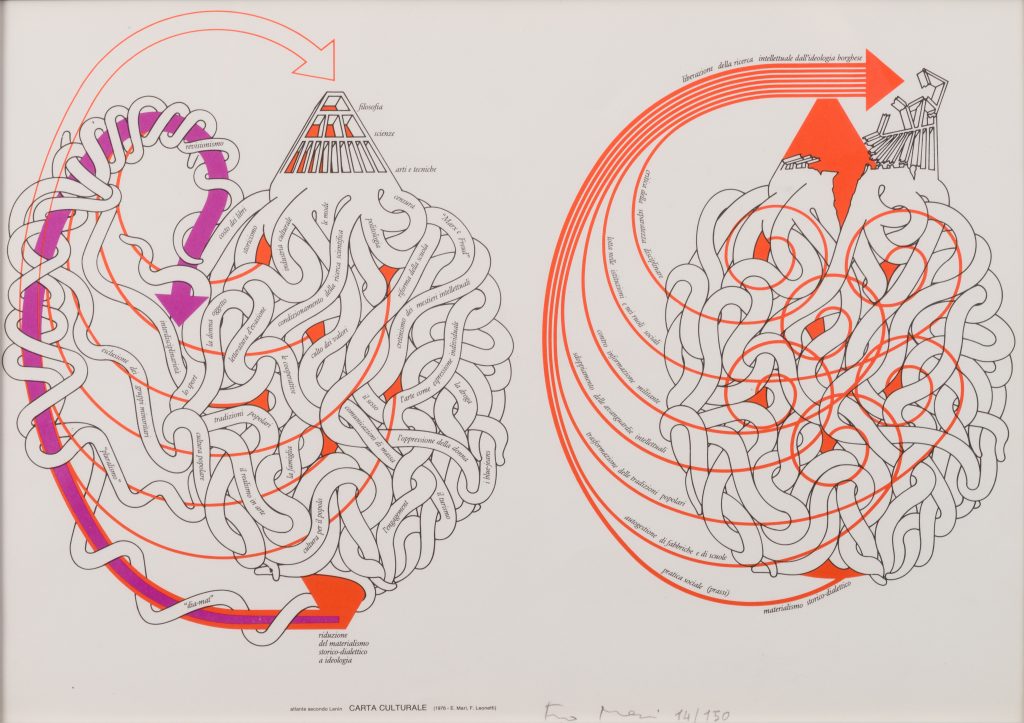

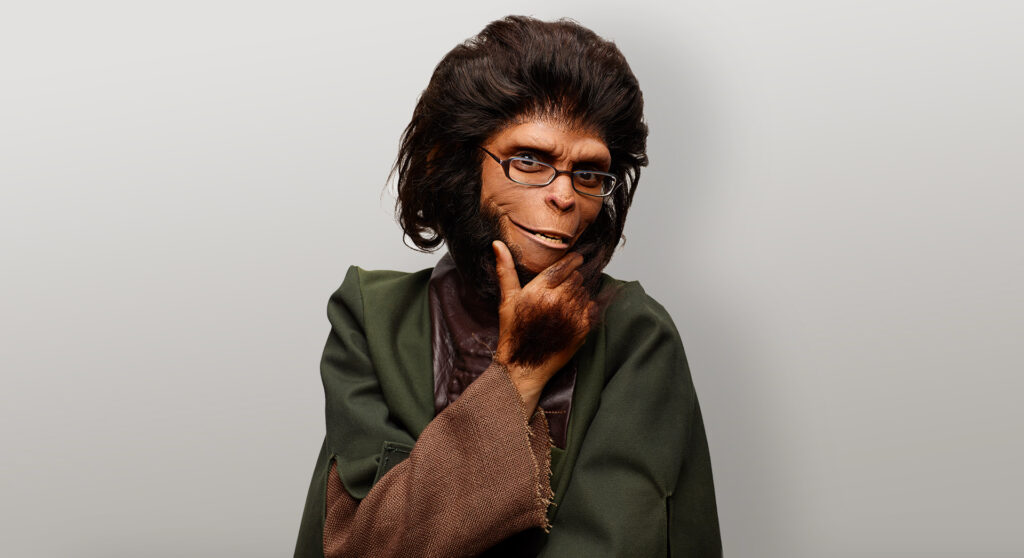

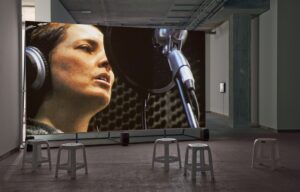

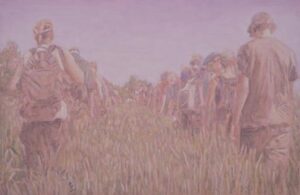

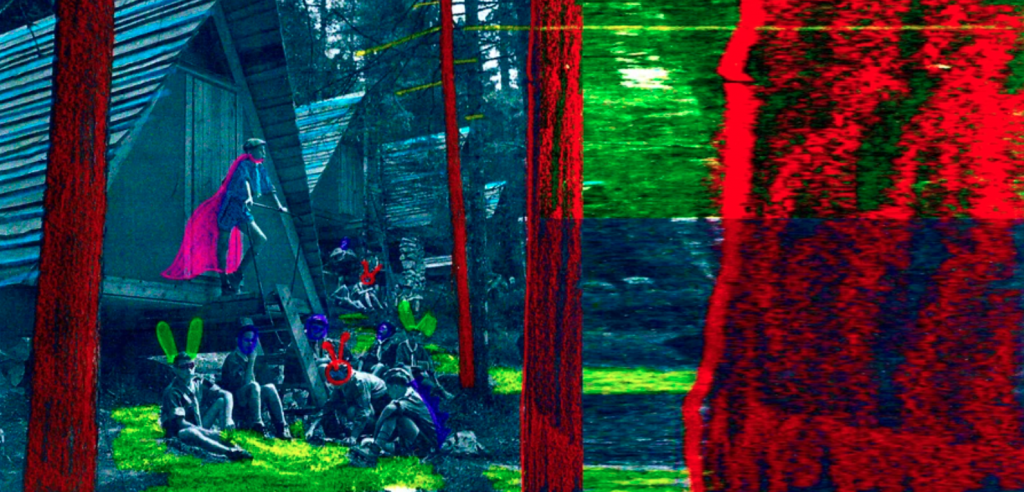

On False Tears and Outsourcing – Dancers Responsible For Delivering Self-Organized Efforts To Resolve Difficult And Time Consuming Issues ‘Go The Distance’Across Multiple Overlapping Phases Using Appropriated Competitive Strategies And Appropriated Intimate Gestures, 2016 dancers, wall of acoustic panels, daylight work lamps and fixtures, live radio, invisible in-ceiling speakers, museum glass. Exhibition view, “Cally Spooner On False Tears and Outsourcing”, New Museum, NY, USA, 2016 Photo: Jeremiah Wilson

On False Tears and Outsourcing – Dancers Responsible For Delivering Self-Organized Efforts To Resolve Difficult And Time Consuming Issues ‘Go The Distance’Across Multiple Overlapping Phases Using Appropriated Competitive Strategies And Appropriated Intimate Gestures, 2016 dancers, wall of acoustic panels, daylight work lamps and fixtures, live radio, invisible in-ceiling speakers, museum glass. Exhibition view, “Cally Spooner On False Tears and Outsourcing”, New Museum, NY, USA, 2016 Photo: Jeremiah Wilson

Courtesy of New Museum, New York.

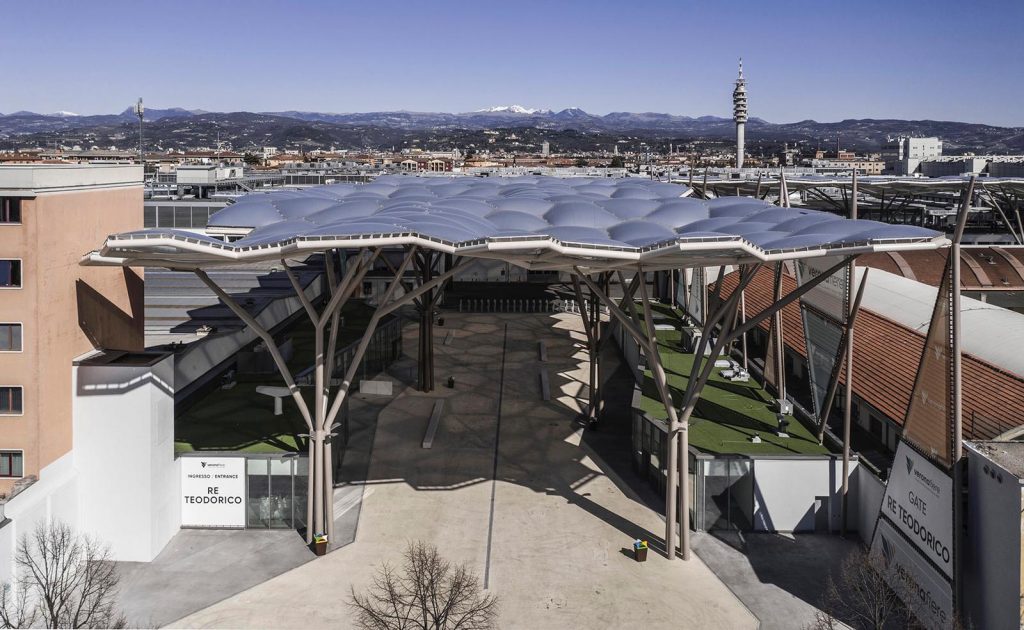

Artist and writer, Cally Spooner (Ascot, UK, 1983) lives between London and Athens. Soon to be involved in Interactions, performance program at the Art Institute of Chicago with her new work DEAD TIME (a crime novel), the artist has recently shown her work at the Castello di Rivoli Museo d’Arte Contemporanea as the winner of the illy prize 2017, the prize that each year, during the Artissima fair, selects the most promising artist within the Present Future section.

Cally Spooner is a careful observer of the air that we breathe each and every day or, using a term that we find many times in her interview, of the “info-sphere” which, as a result of the evolution of the information channels and of their transformation in an increasingly structured economy of data, invisibly wraps our body, enters our organs and stresses their functioning. The info-sphere is only one of the images used by the artist to talk about the oppression that comes from the intensifying of our performance in time. While the issue of productivity and efficiency was at first a request tied to the hours dedicated to wage labour, it now extends to every moment of every day thanks to a technology that is capable, thorough human consent, of monitoring each one of our steps and every minute of our sleep.

If in certain artworks, like Soundtrack for a Troubled Time, 2017, the theoretical analysis concentrates on the causes of specific kinds of physical pathologies, in others the spectator is captured by the artist’s attempts to overthrow a certain kind of “crononormativity” and the consequences it inflicts to society when it becomes an instrument for the development of a certain economic and political model, that of neoliberalist capitalism.

Spooner, thanks to a careful research on the space and time of performance, tries to experience and act out those hidden temporalities in which the body is invited to live rhythms and durations that are different from those that are practiced in daily life. While reading the interview, it seems central for the artist to go back to thinking about the subject from a neo-historical perspective in which self-care becomes a fundamental practice of reappropriation of certain times of the mind like attention, or body movements like micro endurances and repetitive actions.

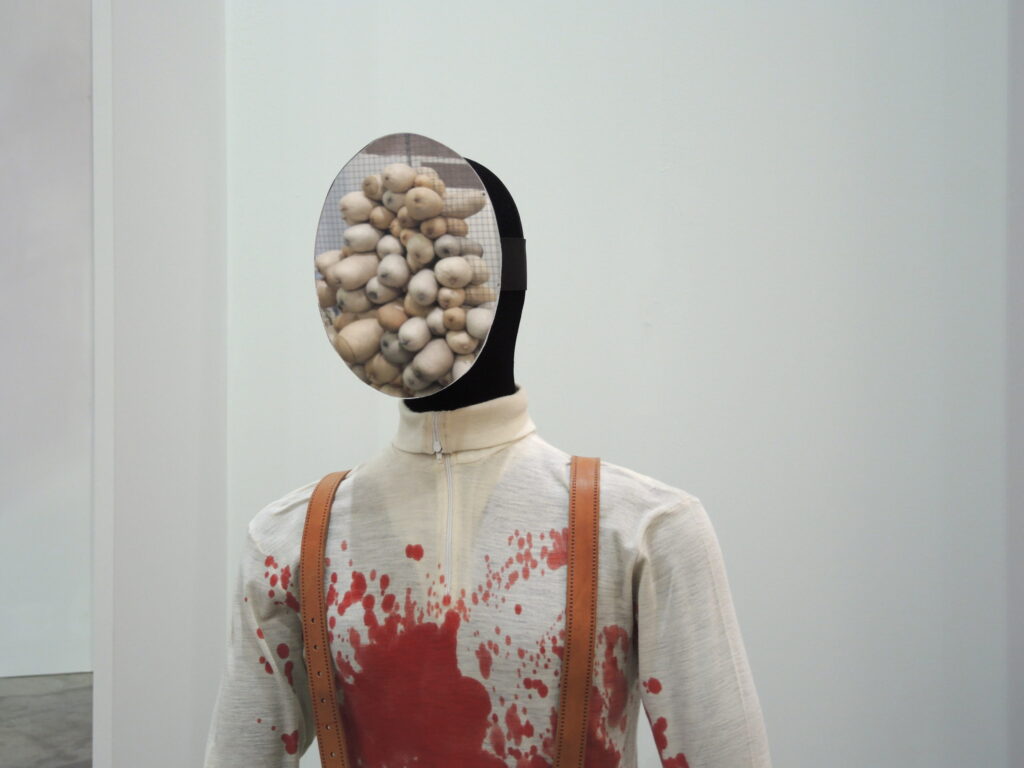

Whereas self-care becomes the instrument of a specific algorithmic accompaniment to life, it also becomes primary to reflect on the action around which revolves one of Spooner’s most recent works, that is the act of spilling and overflowing. In the exhibition project Everything Might Spill both the written element, Diagram of Power, 2018, and the installation Murderous Public Drinking Fountain, 2018, suffer a standstill in their usual function. The scientific language explaining the body is erased, modified and revised by hand; a drinking fountain far from the public space to which it should be destined spills water that has become poisonous with an excess of chlorine. The field of the absurd, often investigated and rebuilt by the artist, opens to moments of “overflowing” in which it seems possible to rediscover a body as last witness.

Caterina Molteni: In the contemporary debate of the last ten years, the advent of the Internet and the development of the digital economy have been re-readed. From tool of freedom and self-organization of knowledge, it has been conceived as a space of control and as last affirmation of neoliberal capitalism. This apparent invisibility of the network has been contrasted by a new thought related to the body. Soundtrack for a Troubled Time, 2017, illy 2017 Award, is composed of a written dialogue between you and the psychoanalyst Isabel Valli in which the issue of hysteria and its preverbal communication, of its invisible manifestation, is dealt with. Do you think that the body, due to its incapacity of a deep fiction, can preserve the ultimate level of resistance towards the complexity of economic, political and social relations? A last witness, a body in which the dizziness of subjectivity is revealed?

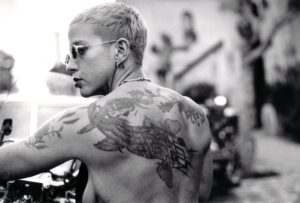

On False Tears and Outsourcing – Dancers Responsible For Delivering Self-Organized Efforts To Resolve Difficult And Time Consuming Issues ‘Go The Distance’Across Multiple Overlapping Phases Using Appropriated Competitive Strategies And Appropriated Intimate Gestures, 2016 dancers, wall of acoustic panels, daylight work lamps and fixtures, live radio, invisible in-ceiling speakers, museum glass. Exhibition view, “Cally Spooner On False Tears and Outsourcing”, New Museum, NY, USA, 2016 Photo: Maris Hutchinson / EPW Studio

On False Tears and Outsourcing – Dancers Responsible For Delivering Self-Organized Efforts To Resolve Difficult And Time Consuming Issues ‘Go The Distance’Across Multiple Overlapping Phases Using Appropriated Competitive Strategies And Appropriated Intimate Gestures, 2016 dancers, wall of acoustic panels, daylight work lamps and fixtures, live radio, invisible in-ceiling speakers, museum glass. Exhibition view, “Cally Spooner On False Tears and Outsourcing”, New Museum, NY, USA, 2016 Photo: Maris Hutchinson / EPW Studio

Courtesy of New Museum, New York.

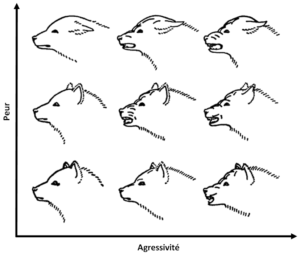

Cally Spooner: The dialogue is Notes on Humiliation (2017). It’s excerpted from a year-long interview with psychiatrist Dr. Isabel Valli about moments when a body becomes captive or static due to stress, psychological disorders or (in the case of a social body) when it is kettled during protest, or when it experiences, say, austerity measures. The dialogue is overlaid with my pretty rudimentary line drawings of human organs involved in the production and circulation of stress. We discuss moments in which usually invisibly functioning systems (the endocrine and nervous system) symptomatically act up or act out at a personal or societal level. In doing so, they become symbolically visible, both bodily and publicly, yet their message may not necessarily be seen or listened to.

The interview took place in London, a city which used to be my home and where I am from. Isabel and I worked from the premise that this city is an “info sphere” of significant size, with a “deep infospheric crust”. The info-sphere includes not just cyberspace, but analogue and off-line spaces of information also. A 1971 Time Magazine book review by R. Z. Sheppard, includes the first documented use of the term, it runs like this:

«In much the way that fish cannot conceptualise water or birds the air, man barely understands his info-sphere, that encircling layer of electronic and typographical smog composed of clichés from journalism, entertainment, advertising and government».

Such smog amounts to an acceleration and intensification of nervous stimulants on persons who find themselves within information, communication and data-heavy centres (including technologically advanced cities such as London or extensive online/digital spaces). My conversation with Isabel began from a simple question: in what ways do immaterial environments and climates leave physical impacts on a body?

When a climate in which a body resides is filled with an acceleration and intensification of nervous stimulants, and (often irrational or injurious) calls for productivity, that climate can easily and accidentally, become an instrument of social control and incarceration (even while it promises a lot of freedoms). Our dialogue explored over-burdened attentions, over-work, stress, how a body becomes weakened or depleted, or the experiencing of illness and forgetfulness when the stress of the infosphere increases. From this, I wanted to understand the moments when scientifically, neurologically and biologically the body (be that individual or collective) leaks, or stalls, or spills within that climate and whether this could be called a subconscious resistance.

Though it’s since moved far away from this, the sound piece you mention has its origins in a reading, in which a performer would censor and erase my language (by running in circles backwards around me, counting loudly) while I was trying to read my writing aloud. I borrowed this trope for Soundtrack for a troubled time (2017) where a performer counts in his native Spanish in the right channels of the sound system. His numerical monologue is choked by barrages of water being bucketed over him. From the left channel, the sound of a game of golf is obliviously and relentlessly played. Abstract language and numbers disintegrate while the presence of a breathing, choking body is increased and rendered as a fiction.

On False Tears and Outsourcing – Dancers Responsible For Delivering Self-Organized Efforts To Resolve Difficult And Time Consuming Issues ‘Go The Distance’ Across Multiple Overlapping Phases Using Appropriated Competitive Strategies And Appropriated Intimate Gestures, 2016 dancers, wall of acoustic panels, daylight work lamps and fixtures, live radio, invisible in-ceiling speakers, museum glass. Exhibition views, “Cally Spooner On False Tears and Outsourcing”, New Museum, NY, USA, 2016 Photo: Luis Antonio Ruiz / Matte Projects

On False Tears and Outsourcing – Dancers Responsible For Delivering Self-Organized Efforts To Resolve Difficult And Time Consuming Issues ‘Go The Distance’ Across Multiple Overlapping Phases Using Appropriated Competitive Strategies And Appropriated Intimate Gestures, 2016 dancers, wall of acoustic panels, daylight work lamps and fixtures, live radio, invisible in-ceiling speakers, museum glass. Exhibition views, “Cally Spooner On False Tears and Outsourcing”, New Museum, NY, USA, 2016 Photo: Luis Antonio Ruiz / Matte Projects

Courtesy of New Museum, New York.

C. M.: In your recent interview for «Mousse Magazine», you discussed the concept of “chrononormativity” emphasising that «in its simplest terms it’s all running on the same clock, this clock can often make invisible things that are slower and more durational, such as maintenance». Beyond the consequences in History and its linear development chosen by the human being, this chronormativity is also supported by the perceptual model of the digital that today seems to become the unique for everyone. How is it possible, in your opinion, to escape from this perceptual and sensitive impoverishment? Contemporary criticism, in particular we can think of the thought linked to the speculative fabulation of Donna Haraway, proposes in contrast a narrative thought which is another fundamental element of your work.

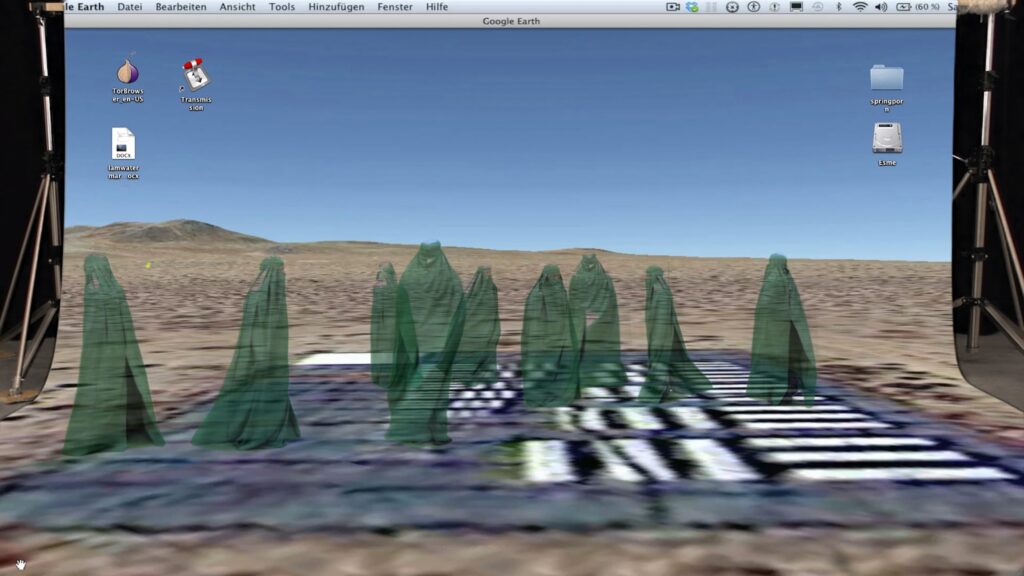

On False Tears and Outsourcing – Dancers Responsible For Delivering Self-Organized Efforts To Resolve Difficult And Time Consuming Issues ‘Go The Distance’ Across Multiple Overlapping Phases Using Appropriated Competitive Strategies And Appropriated Intimate Gestures, 2016 dancers, wall of acoustic panels, daylight work lamps and fixtures, live radio, invisible in-ceiling speakers, museum glass. Exhibition views, “Cally Spooner On False Tears and Outsourcing”, New Museum, NY, USA, 2016 Photo: Luis Antonio Ruiz / Matte Projects

On False Tears and Outsourcing – Dancers Responsible For Delivering Self-Organized Efforts To Resolve Difficult And Time Consuming Issues ‘Go The Distance’ Across Multiple Overlapping Phases Using Appropriated Competitive Strategies And Appropriated Intimate Gestures, 2016 dancers, wall of acoustic panels, daylight work lamps and fixtures, live radio, invisible in-ceiling speakers, museum glass. Exhibition views, “Cally Spooner On False Tears and Outsourcing”, New Museum, NY, USA, 2016 Photo: Luis Antonio Ruiz / Matte Projects

Courtesy of New Museum, New York.

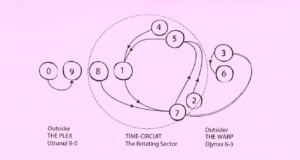

C. S.: Chrononormativity is the process used to organise bodies towards maximum profitability, where all life is engineered to run on the same clock; a clock set by those in power, to grant maximum control, efficiency and profit. Chrononormativity hooks up neatly with western conceptualization of linear time, which pronounces times to be organised around discreet categories of past, present, future. Stemming from European Judea-Christian traditions, time is experienced as an inevitable flow towards a divinely ordained future. Capitalism incorporated this future-oriented linearity into labor and production as it began to regulate time more precisely through mechanical clocks, calendars, bells; moving from nature-based timekeeping (beginning and ending work with the sun) to mechanical clock time. Western time is intimately tied to the histories of capitalism.

Today these powerful rhythms, and the logic of mechanical time, remain. Even if intermittent push notifications on our phone seem uniquely tailored to us, and appear to give us a lot of flexibility over how we handle our own apparently unique experiences of time, they really coerce us into a rhythm that puts us on a certain psychic register or wavelength at the level of consciousness (while taking away our attention). This is a rigid, productivisit temporality, that constantly projects us into the future, a place where we are not. Figuring out ways to future-proof outcomes is the essence of advanced computation. This is the capability to model, predict and thus control the outcome of events. It’s the logic on which the digital age is premised.

The pervasive logic today is that the future is something that can be predicted and modelled if only enough data can be gathered. This is computational time and we all live inside it. Data science and predictive software means that our day to day activities are based around anticipating or predicting the future more, and uncertainty is often presented as an information problem that can be overcome with comprehensive data analysis, thereby undoing the existential terror of not knowing what is going to happen (take predictive policing as one example).

In this climate, I’m interested in what practices manage to engage in hidden, present-tense temporalities, which can reveal diverse and contradictory ways that time is lived and experienced. I understand those to be the hidden temporalities embedded in the labour of rehearsal, attempting, continuing, persisting, staying, enduring and waiting. Perhaps these things seem to appear at first glance to also be without qualities, stuck and suspended. But these are what allow us to grasp alternative forms of time as a duration and to think about the relation between bodies that desist, and the kinds of obdurate temporalities that desisting bodies perform.

Desisting bodies ask us to think about the slowness of chronic time; the durational drag of staying alongside others or out-of-date ideas. We could call this form of time “staying power” or Donna Haraway’s expression “staying with the trouble”. I like to think that in this staying power is a kind of “life drive” or, in other words, kept in a state of “ongoingness”, which returns us to sense of place in which we may observe, document and think clearly, in present time, and therefore exercise stewardship (not only of the changing planet and its climate) but also to our attentions, our minds and our handling of time.

Exhibition view, “Cally Spooner: SWEAT SHAME ETC.”, Swiss Institute, New York, USA, 2018 Photo: Daniel Perez. Courtesy of the artist, gb agency, Paris and ZERO…, Milan.

Exhibition view, “Cally Spooner: SWEAT SHAME ETC.”, Swiss Institute, New York, USA, 2018 Photo: Daniel Perez. Courtesy of the artist, gb agency, Paris and ZERO…, Milan.

C. M.: The exhibition project at the Castello di Rivoli is entitled Everything Might Spill. The fountain on display seems to allude to an interference in the perfect project of the total “cleaning” and “computing” operation of neoliberal industry. Would you like to talk about this exhibition that will open? In particular, I’m fascinated by the concept of “spill”, and how can it be seen as a possibility to interfere and make changes?

Self Tracking, 2018 (detail), Sienna X express tanning mist streak free natural color, pencil, colored pencil, data from the artist`s metabolism (2013 – 2018), data from Artfacts.net on the artist’s career rank, (2013-2018), data from XE The World’s Trusted Currency Authority on the British Pound measured against the Euro (2013-2018). Exhibition view, “Cally Spooner: SWEAT SHAME ETC.”, Swiss Institute, New York, USA, 2018 Photo: Daniel Perez. Courtesy of the artist, gb agency, Paris and ZERO…, Milan.

Self Tracking, 2018 (detail), Sienna X express tanning mist streak free natural color, pencil, colored pencil, data from the artist`s metabolism (2013 – 2018), data from Artfacts.net on the artist’s career rank, (2013-2018), data from XE The World’s Trusted Currency Authority on the British Pound measured against the Euro (2013-2018). Exhibition view, “Cally Spooner: SWEAT SHAME ETC.”, Swiss Institute, New York, USA, 2018 Photo: Daniel Perez. Courtesy of the artist, gb agency, Paris and ZERO…, Milan.

C. S.: The spill I borrowed from Anne Carson. It arises in an essay she wrote on The Sublime in her book, Decreation. The sublime is a moment to make, as she puts it, foam, or spillage: «Longinus’ treatise on the sublime is an aggregation of quotes. It has muddled arguments, little organization, no paraphrasable conclusion. Its key topic, passion, is deferred to another treatise which does not exist. You will come away from reading its unfinished 40 chapters with no clear idea of what the sublime actually is, but you will have been thrilled by its documentation». She says.

She also refers to Michelangelo Antonini’s creation of spillage through his use of the cinematic trope, Temps Mort or Dead Time, in which he leaves the camera running even after the scene is finished and the actors have finished acting. Here, in this elongated shot, the actors continue out of inertia into moments that seem “dead”. The actor commits error. Anne Carson describes it like so: «Later he took to letting the shot run even after the actors had made their exit. As if for a while something might be still rustling around there in an empty doorway». This rustling in an empty doorway, the less controlled, this staying power, and the possibility of opening up the very unexpected, like Longinus’ aggregation and deferral, is spillage.

At Rivoli I made two works; Murderous Public Drinking Fountain, an absurdist, silent killer in a in a crime scene set somewhere between the 4th Industrial Revolution and the 6th Extinction. This stainless-steel drinking fountain with its faucet jammed, is perpetually running. Disconnected from any public water source, the fountain is fed from its own supply of chlorinated water, continuously cycling a hygienic yet poisonous agent through itself. Barely water, mostly chlorine, the fountain stinks of hygiene. On the wall, is Diagram of Power, 2018’. This fictional ‘expert witness report’ on paper, hosted in plastic sleeves, describes a female body that is a witness, a victim and also a killer. In the Diagram of Power this female subjects takes multiple forms, at times an environmental crisis, at others an economic condition, often she’s described as an organ that may or may not filter, cleanse, nourish, leak, spill and poison herself or others. The typed and printed text, which originates from medical research on body organs – their representation and maintenance from Hippocrates and beyond –, is interfered with; corrected, erased and censored by hand writing. Beneath the pages of text is a wall drawing of a liver. It is executed oversized and rudimentary as a jagged red line scraped over the gallery wall.

The spill exists formally in the show, I guess in the sense that, In Diagram of Power, the text is interfered with. The orginal typed text is fractured and leaked, by last minute changes of mind. The fountain reveals its insides; its pipes are pulled out, it’s inside plumbing trailing outside revealing that this metal and rubber body is an absurd fiction, getting more poisonous through its one-channel relationship with itself. Absurdity is, I hope, one way of creating a spillage. Equally the “spill” at Rivoli is a call for the temporally rigid regimes of self-management and for invisible carceral power to fail because if it fails, what might open up and spill out is a deep-time care and stewardship of the subject, others, and the earth on which the subject and its others temporarily resides. Going back to the conversation with Isabel I am interested in those moments the body grinds to a halt, refuses, and acts out or up or leaks out, because it desires to generate something beyond the rubric of the chrononormative clock, beyond the infosphere smog, and beyond its status as a captured attention and body.

On speakers: He wins every time, on time and under budget, 2016. Amplifier, two Bose 5 second-generation. Virtually Invisible® cube speakers, stereo audio. Courtesy of the artist and gb agency, Paris. On wall: Self Tracking, 2018. Sienna X express tanning mist streak free natural color, pencil, colored pencil, data from the artist`s metabolism (2013 – 2018), data from Artfacts.net on the artist’s career rank, (2013-2018), data from XE The World’s Trusted Currency Authority on the British. Pound measured against the Euro (2013-2018). Courtesy of the artist, gb agency, Paris and ZERO…, Milan. Exhibition view, “Cally Spooner: SWEAT SHAME ETC.”, Swiss Institute, New York, USA, 2018 Photo: Daniel Perez

On speakers: He wins every time, on time and under budget, 2016. Amplifier, two Bose 5 second-generation. Virtually Invisible® cube speakers, stereo audio. Courtesy of the artist and gb agency, Paris. On wall: Self Tracking, 2018. Sienna X express tanning mist streak free natural color, pencil, colored pencil, data from the artist`s metabolism (2013 – 2018), data from Artfacts.net on the artist’s career rank, (2013-2018), data from XE The World’s Trusted Currency Authority on the British. Pound measured against the Euro (2013-2018). Courtesy of the artist, gb agency, Paris and ZERO…, Milan. Exhibition view, “Cally Spooner: SWEAT SHAME ETC.”, Swiss Institute, New York, USA, 2018 Photo: Daniel Perez

Cally Spooner (1983) è un’artista e ricercatrice inglese. Il suo lavoro è stato presentato in numerose mostre in importanti gallerie e musei, tra cui il New Museum di New York, l’Art Institute of Chicago, Stedelijk Museum di Amsterdam e la Whitechapel Art Gallery, Londra. Nella sua pratica artistica unisce in modo non sincronizzato citazioni, trattati teorici, film, canzoni pop o talk show attraverso produzioni dal vivo, installazioni cinematografiche, coreografie, letture e script. Tra le sue pubblicazioni: Scripts (2016) e il romanzo Collapsing In Parts (2012).

Elena D’Angelo è producer ed editor freelance. Dopo la laurea triennale in Scienze dei Beni Culturali presso l’Università Statale di Milano ha frequentato il biennio specialistico in Visual Cultures e Pratiche Curatoriali presso l’Accademia di Belle Arti di Brera. Ha lavorato come producer presso il Castello di Rivoli Museo d’Arte Contemporanea, seguendo progetti di numerosi artisti internazionali come Anri Sala, Hito Steyerl, Nalini Malani e Cécile B. Evans. Al momento collabora con Mattatoio (Roma) ed è partner dell’archivio video online instudio.

More on Magazine & Editions

Magazine , ESCAPISMI - Part I

Sparire dentro un pixel

Pratiche di in-visibilità a partire da “How not to be seen: a fucking didactic educational.mov file”

Magazine , ESCAPISMI - Part I

Spettacolarizzazione del conflitto

Strategie di coping nell’epoca della necropolitica

Editions

Printed edition

Assedio e mobilità come modi per stare al mondo: le prime ricerche di KABUL in edizione limitata.

Editions

Utopia on now. Dalle avanguardie artistiche all'utopia del fallimento

Excursus teorico dalla definizione di utopia classica al suo fallimento e alla sua ridefinizione

More on Digital Library & Projects

Digital Library

Imitazione di un Sogno

Esplorazioni filosofiche e sensoriali tra sogno e realtà.

Digital Library

Ne Quid Nimis. Sull’opera di Walter Swennen

Prefazione di Luca Bertolo.

Projects

Le forme pop della didascalia

L’uso della didascalia nel contesto museale e la descrizione dell’immagine nell'epoca della cultura visiva: una riflessione scaturita dal secondo appuntamento di Q-RATED (Quadriennale di Roma).

Projects

Sconfiggere il populismo sovranista con il linguaggio esoterico dell’arte contemporanea e la collaborazione dei musei

Quali sono i diversi approcci adottati da curatori e direttori di musei per condurre un workshop nella propria istituzione? Una riflessione scaturita da Q-RATED, il programma di workshop organizzato da Quadriennale di Roma.

Iscriviti alla Newsletter

"Information is power. But like all power, there are those who want to keep it for themselves. But sharing isn’t immoral – it’s a moral imperative” (Aaron Swartz)

KABUL è una rivista di arti e culture contemporanee (KABUL magazine), una casa editrice indipendente (KABUL editions), un archivio digitale gratuito di traduzioni (KABUL digital library), un’associazione culturale no profit (KABUL projects). KABUL opera dal 2016 per la promozione della cultura contemporanea in Italia. Insieme a critici, docenti universitari e operatori del settore, si occupa di divulgare argomenti e ricerche centrali nell’attuale dibattito artistico e culturale internazionale.