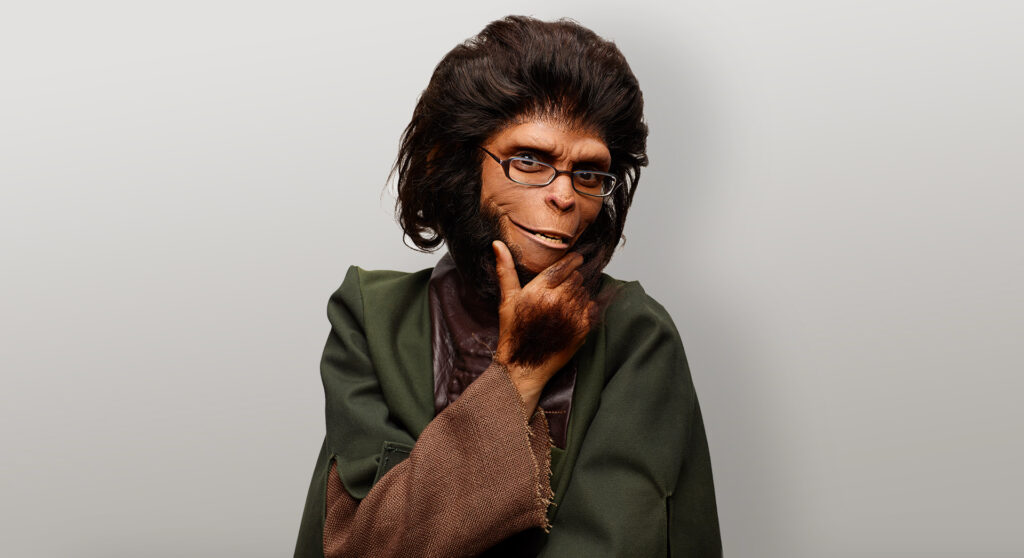

McDonald’s sign in the middle of a desert near the Dead Sea.

McDonald’s sign in the middle of a desert near the Dead Sea.

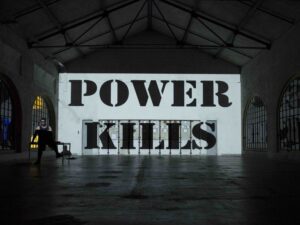

«The most beautiful thing in Tokyo is McDonalds

The most beautiful thing in Stockholm is McDonalds

The most beautiful thing in Florence is McDonalds

Peking and Moscow don’t have anything beautiful yet.

America is really The Beautiful».

(A. Warhol, 1975)

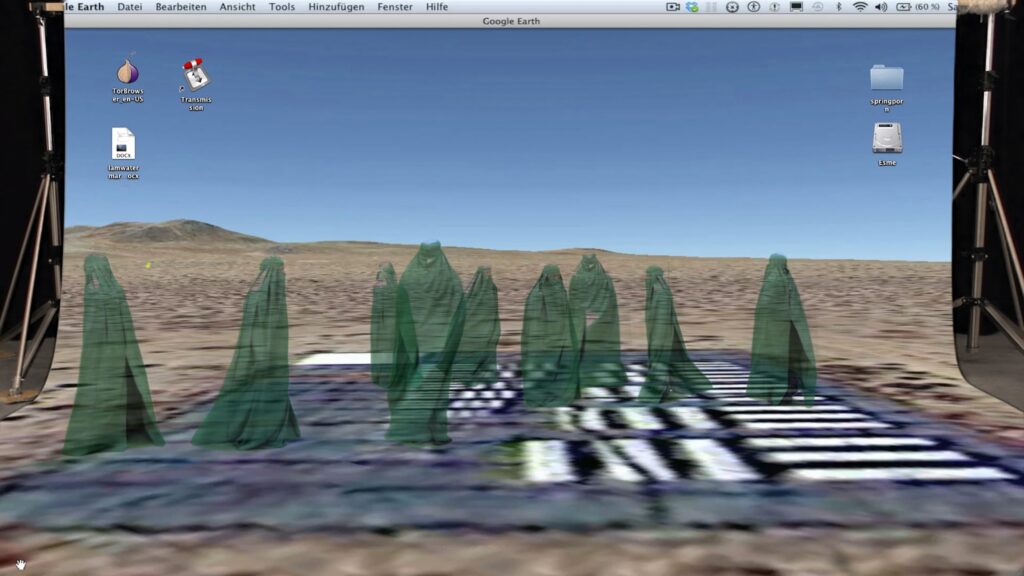

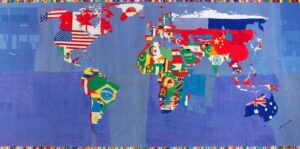

«The times in which we live are thus an era of postromantic, that is comfortable and total, tourism, marking a new phase in the history of the relations between the urban ou-topos and the world’s topography. This new phase is in fact not hard to characterize: rather than the individual romantic tourist, it is instead all manner of people, things, signs and images drawn from all kinds of local cultures that are now leaving their places of origin and undertaking journeys around the world».

(B. Groys, The City in the Age of Touristic Reproduction, 2002)

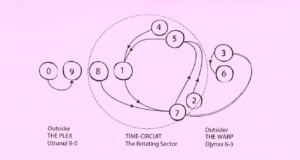

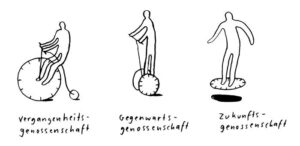

In the essay The City in the Age of Touristic Reproduction, Boris Groys communicates the circulation starting point of all the elements, natural and architectural, that before were known like typical of just a few specific territorial realities. Following this spreading phenomenon, images that were seen only in a defined part of the world are now common everywhere, due to Internet and Globalization. Consequently the artists’ touristic activity has changed. The traveller who is in search of new forms for his studies becomes from being ‘romantic’ to ‘comfortable and total’.11See J. Schlosser Magnino, La letteratura dei Ciceroni, in Letteratura artistica (1924), La Nuova Italia, Milan, 2008, pp. 534-553; C. De Seta, L’Italia del Grand Tour (1995), Rizzoli, Milan, 2014.

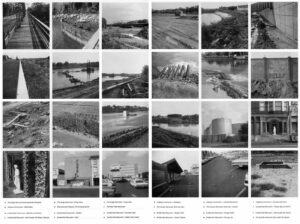

Romantic tourists used to pick up and record landscape peculiarities from the field, tracking for the first time traits of a national identity that just at a later time will be known as Italy.22In the back cover of De Seta’s book, it is written: «Italy builds its identity as a mirror reflection: since the sixth to the end of the eighth century, the tourists used as a means to travel, and relate, paint, and allow the culture to flourish in society. In this way, before our nation was founded. In this way ‘Bella Italia’ was born, even before our nation was born. In the meantime began the sowing of the seeds of the European identity that we still miss. They are present in the cultural impassioned tales of these exceptional travellers and it is possible to trace them».

On the contrary the artists who are living in the post-romantic era, according to Groys’s definition, «thanks to modern means of communication they can seek out like-minded associates from all over the world instead of having to adjust to the tastes and cultural orientation of their immediate surroundings».33B. Groys, The City in the Age of Touristic Reproduction, in Art Power, MIT Press, Cambridge (Mass.), 2008, p. 105.

For this reason, speaking now about artistic communities and regions with their own identities is impossible. This could sound as much anachronistic as pathetically nostalgic.

We can suppose that in Italy the date of the transition moment between the two kinds of artistic tourisms is 1967, when Piero Gilardi started to work as news correspondent for «Flash Art International» and he used to update his Italian friends and art dealers about the American scenario. In this way Gilardi was the first to develop an international network, but that chat space was still limited to a closed group of people who were living in the same city.44«The aim of my trips, from the United States to Europe, was to help the development of an artists’ network active in the new trends but free and independent of the artistic market. I used to travel with a photo dossier including works of around forty artists, in order to show how an artistic movement was growing with a deep conceptual unity.» A. Bellini, Piero Gilardi: Ora cammino senza più allacciarmi le scarpe, in «Flash Art Online», April 2012.

On one hand, the distended transmission times gave the possibility to metabolize slowly and personally all the foreign news with the local ordinary life; on the other hand, thanks to the new communication tools and means of transportation, some exhibition display standards, and brand-new works of art and theories started to circulate quicker with respect to the Grand Tour times.

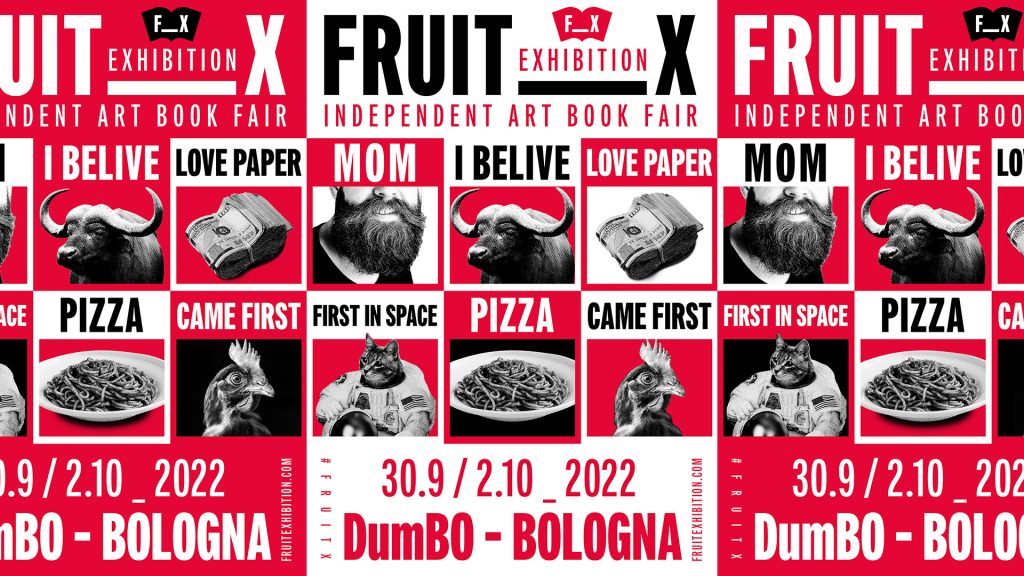

In the actual post-romantic era the artist-tourist, and the curator-tourist as well (and all the people involved in the production art field), have joined the frenetic kind of tourism. We are obligated to see a landscape populated by homologate forms, all the same everywhere. Those forms are temporary, threatened by the speed of the global production that forces them to live in a never-ending state of changing. The travel modality and approach are now mutated.

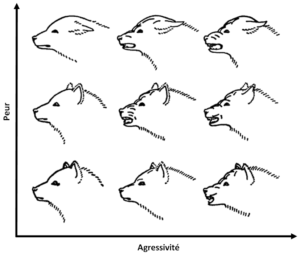

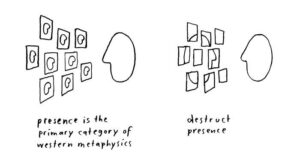

The thing that is not changed is the artistic and curatorial production activity of picking-up and translation of visible forms present in the landscape. The trend of the homologation of forms in the cities has a reflection in the artistic production. But, what makes the works different if they all look the same? Arthur C. Danto, in the first chapter of his book The Transfiguration of the Commonplace, with a complete different aim, draws up a checklist of a hypothetical exhibition curated by himself: every piece of work is always the representation of a red square. To the visitor’s gaze everything will look identical concluding that an «retinal indiscrimination»55A. C. Danto, The Transfiguration of the Commonplace, in «The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism», vol. 33, no. 2 (Winter, 1974), p. 140.

is present between the works. This is a problem also for the little collector who, complaining, continues to search the newness of form.

If the works mirror the forms that are living in our times, then the outbreak of a unique ‘aesthetic’ can be easily justified. In our days, the artistic debate is on a global layer and every singular identity is hidden inside each work of art: the same concrete block used in the last ten years by more than four divers artists has inside more than four different stories. According to that, each block will be considered as unique. Given that the shape of the work is uniform, recalling that those forms are temporary means that the shape they have in common is the eternal image of a specific landscape different from all the forms that can be found in the remote past or in the future. The fleeting forms present in our real and virtual life, from streets where we walk everyday, to the website that we use to google it as a habit, became symbols of a precise historic period, as a monument, thanks to the artistic process. Indeed we should see the form of the work avoiding draining doubts or cultural games as “Who did it first?” but thinking if we are able to connect some of our personal experiences to that form within we share the landscape. As Vladimir Nabokov said in the introduction of Transparent Things:

«When we concentrate on a material object, whatever its situation, the very act of attention may lead to our involuntarily sinking into the history of that object. Novices must learn to skim over matter if they want matter to stay at the exact level of the moment. Transparent things, through which the past shines!».66V. Nabokov, Transparent Things (1972), Penguin Modern Classics, UK, 2011, p. 5.

Avoiding the fetishism of form and leaving the ‘novices classroom’, we will see that object, part of the collective memory, in a different way. Going deep under its surface it is possible to grasp our story and the story of who has picked up that form from the landscape.