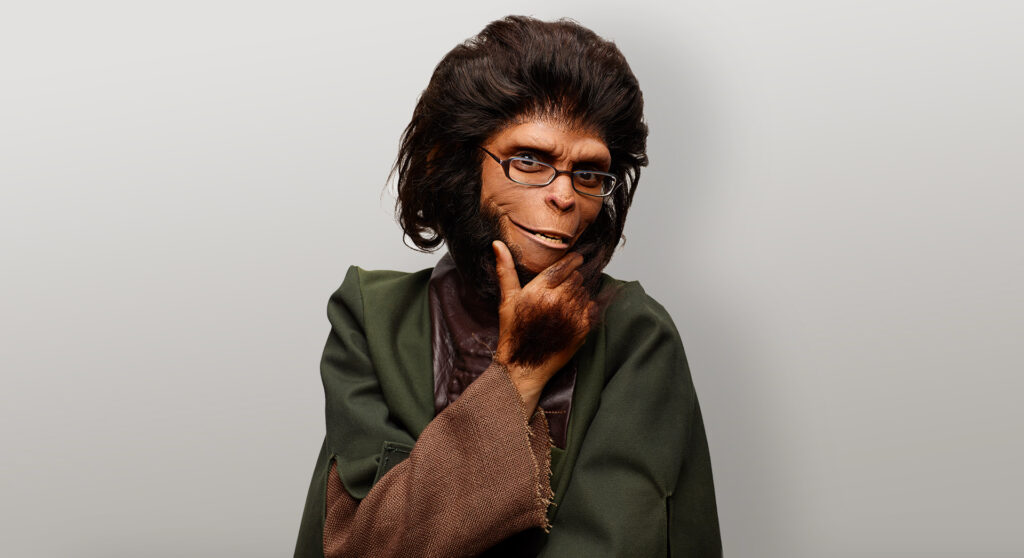

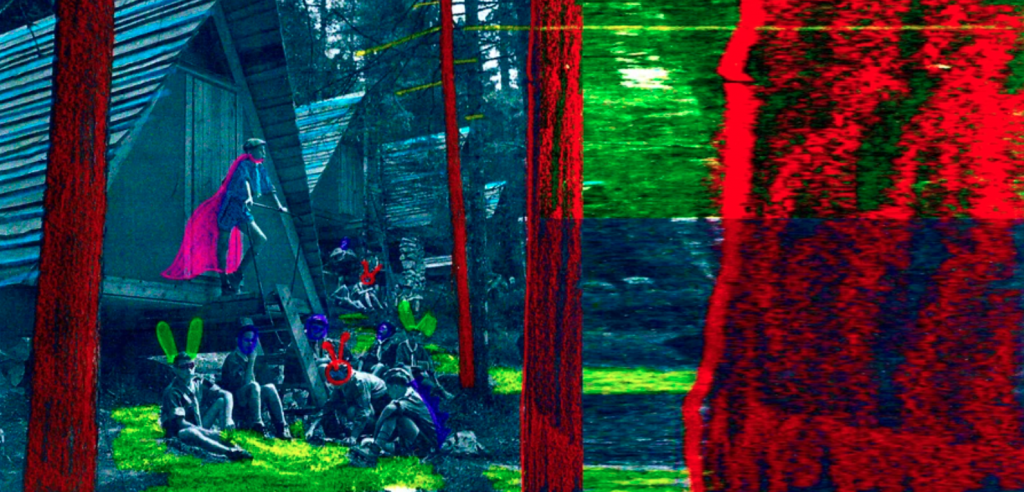

Abounaddara – The team – 11 videos – 2015.

Abounaddara – The team – 11 videos – 2015.

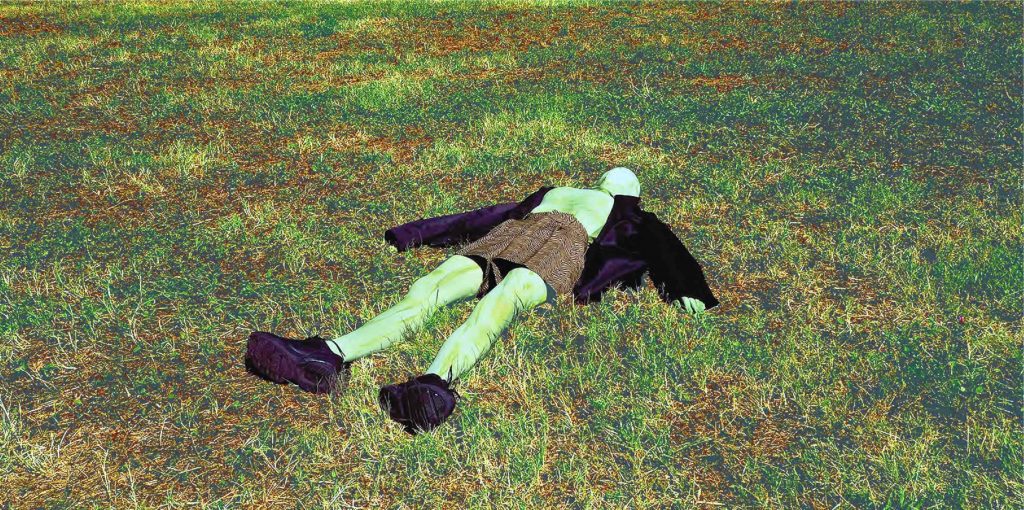

the green soul searching

life where only

bites drought and desolation,

the spark that says

all begins when everything

seems

charred, buried ashes;

(E. Montale, The Eel)

Italy 1945: the memoirs become the preferred genre to tell the horrors of the Nazi-fascism. The end of World War II, with the opening of the concentration camps and extermination, marks the beginning of an indispensable search for truth. Everybody wants to have his say, and the value of the direct testimony is expressed by the widespread dissemination of autobiographical stories, prison diaries and private correspondence. With these words, Italo Calvino lucidly summarizes the Zeitgeist of the period immediately following the end of the conflict: «The literary explosion of those years in Italy was before a fact of art, a physiological fact, existential, collective. […] One was face to face, at par, full of stories to tell, everyone had had her own, everyone had experienced adventurous dramatic irregular lives, we tore the word of mouth. The reborn freedom to speak was for people at the beginning the urge of telling».11I. Calvino, Il sentiero dei nidi di ragno (Preface), Mondadori, Milano 1964, p. VI.

Syria 2011: the outbreak of the civil war, the same «eagerness to tell», which is nothing more than urgency to validate the social and collective history through the stories of those who lived through the events in the first person (the individual history), is expressed by an anonymous collective of activists and Syrian filmmakers who calls itself Abounaddara (literally ‘the man with glasses’).

Defined on several occasions by the collective and its spokesman – Charif Kiwan – as ‘emergency cinema’, Abounaddara was born in Damascus in 2010 with the specific intent to change the way the Syrian civil society is represented by the media and industry culture of the country, now divided between pro-government forces (Syrian armed forces, FND, Shabiha, etc.), anti-government factions (ESL, CNS) and terrorist organizations of Islamic origin (al-Nusra Front, IS and Islamic Front).

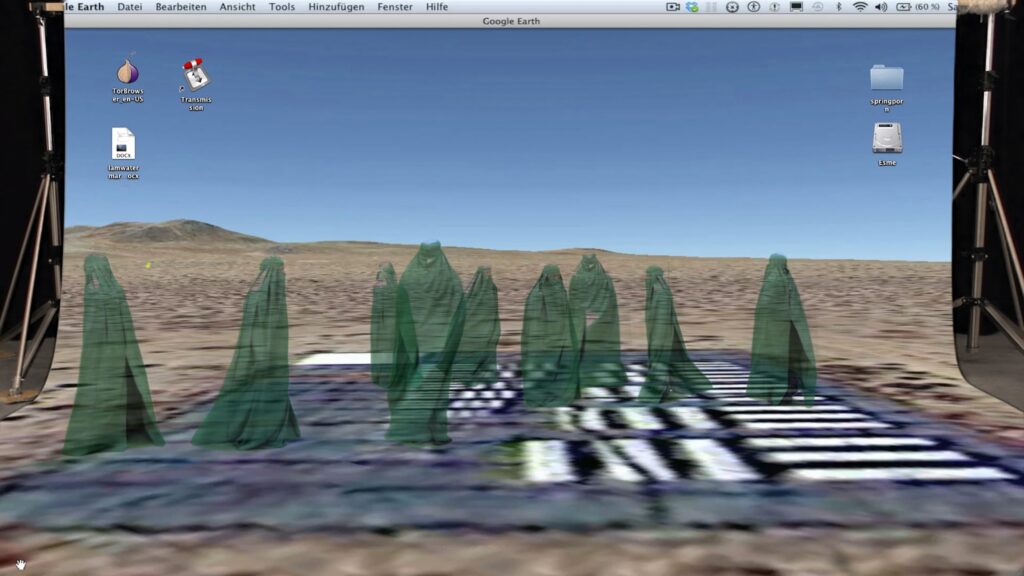

In the recent global ranking of press freedom compiled by Reporters Sans Frontières, Syria figures at the 177th place out of 180 countries surveyed. Television, radio and Internet access are under the full control of the authoritarian regime of Bashar al-Assad. Since the outbreak of the riots in 2011, the state persecution of professional journalists and citizen journalists have been further tightened, causing the arrest, disappearance and in many cases the death of numerous civilians.

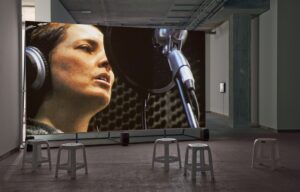

In such context, Abounaddara, not perceiving public funding and not being supported by any production company, it operates entirely outside the cinema economic system. For five years the collective distributes, from its Vimeo account, a new movie a week and promotes itself through its website and social networks (Facebook, Twitter). With nearly 400 short films in assets, with a duration ranging from 20 seconds to 12 minutes approximately, Abounaddara has already been honoured with several awards: in 2014 it won the Grand Jury Prize in the ‘short films’ section of the Sundance Film Festival, for Of Gods and Dogs, a short 12 minutes when a young soldier of the Free Syrian Army admits on camera that he had killed an innocent prisoner; in the same year, it took part in Here and Elsewhere, an exhibition on contemporary Arab world presented at the New Museum in New York and curated by a team led by Massimiliano Gioni; the collective was also awarded the Vera List Centre for Art and Politics Prize, and in 2015 received a special mention at the 56th edition of the Venice Biennale, from which, however, has decided to withdraw its last film because, according to the collective statement, subjected to censorship action.

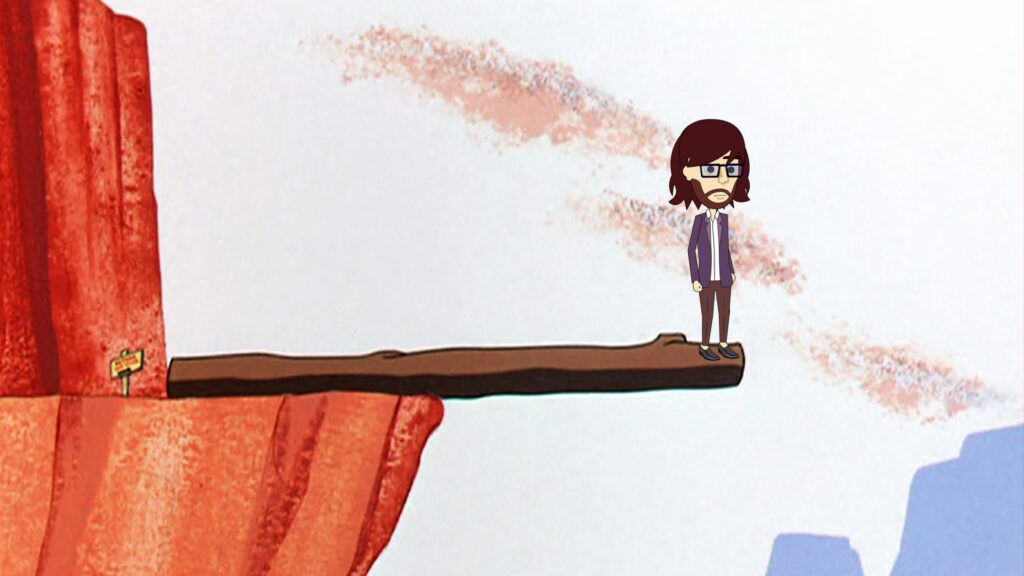

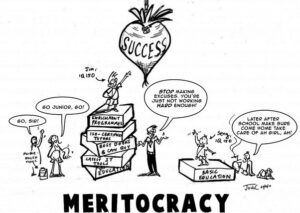

But let us come to the analysis of its film production. In the first place, the Abounaddara film is characterized by its eclecticism and for the absence of a standard language. Departing from the tradition of documentary films, of which the collective intends to exaggerate the boundaries, its video productions reveal a rich variety of stylistic and expressive registers, from the language of photography, that of advertising, video clips, films of propaganda and reportage.

Among the narrative modes adopted let us note of the resumption of everyday scenes and handling and replacement – most often at the end of satirical – of pre-existing video material. Examples of the latter type are Kill Them (2015), a video clip made from this gruesome video where Jeanine Pirro suggests «arming the Muslims to the teeth» [sic!] to come to stop the terrorists’ horrors, and My name is Bashar (2015), a slideshow of 16 images that portray the Syrian dictator from his childhood to adulthood with a soundtrack gooey and sentimental.

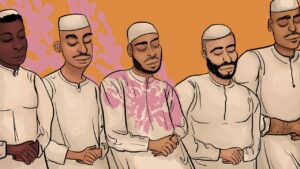

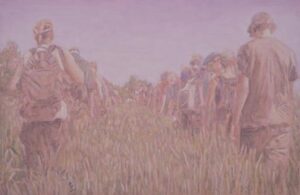

However, the narrative mode remains the most used free interview, in which the protagonist is told in the first person on camera, without the interruption of the voice of the interviewer, removed during assembly. In a country where men of the Caliphate enslave women, Abounaddara shows us the faces of the activists who fight every day for their own self-determination, the voices of the Syrian resistance. Here are some examples.

The protagonist of The Woman in Pants (2013) is called Suad Nofal. She is a former teacher of Raqqa, in 2013 a stronghold of the jihadist militias. After the arrest of her friends and collaborators, the woman found herself alone in its daily against the self-proclaimed Islamic State («a small gang that takes advantage of people’s fear»). According to the words of Suad, what most annoys militiamen is wearing pants, and to the women of Raqqa they are prohibited because they are considered immoral (but the woman asks, «how can be sinful pants and not the mask?»).

In another video, Marcell (2014), an activist from Aleppo arrayed against the Assad regime, openly declares that she stopped wearing the veil since the jihadist troops in her city started to impose it («My goal today is to try to respect society’s traditions. But also society must respect the right to be different from those who think differently»).

In The Lady of Syria (2014), a class of girls is intent on following a course on how to make a perfect wedding hairstyle. It looks like a canonical situation, the teacher leads stoically his lecture addressing the girls with an affable tone and being ironic («War or no war, we’re still hip, right?»). However, the scene takes place in a building dilapidated, which bears the spectre of war, and at the end of the movie we learn that the next day, to escape the threat of new bombings, there will be no lesson.

To the voices of Resistance, Abounaddara also approaches those of jihadist counterparts and those that unfortunately had to do with it. In The Islamic State for Dummies (2014), in what looks like an office, a militiaman explains the difference between traditional Islam and modern – what, according to him, would embody the IS – claiming the need to preserve Sharia for the sake of the population: for example, for a thief, the expected punishment is his hand cut. Those who oppose the punishment, the militiaman, or is a thief in turn, or an individual who does not take responsibility for his actions («Whoever opposes cutting a thief’s hand… If you are against it, it means you are a thief, or that you want to steal without accountability or that you want punishment to be merely symbolic. That is not possible»).

In Voyage to the Islamic State (2015), an activist in Raqqa, with his face obscured, tells of his abduction by the jihadist militias. After the seizure of the phone and the computer, it was brought onto a white car («Everyone from Raqqa has a phobia of those white cars, which they use for abducting activists») and took to the headquarters for questioning. He has not suffered any physical violence, the dormitory where he was transferred was even bigger than the overcrowded cells used by the regime. However, in the last days of his abduction, he and the other detainees have suffered intense psychological pressure, with the forced vision of the movie of the execution of Mu’adh al-Kasasbeh, the Jordanian pilot burned alive inside a cage in January 2015.

Yet, in The Child Who Saw the Islamic State (2015), a man tells us what is living in a city where public executions occur daily, in the main squares and streets of the centre, and that a day he has surprised his son in an attempt to cut the throat of his just two years old sister.

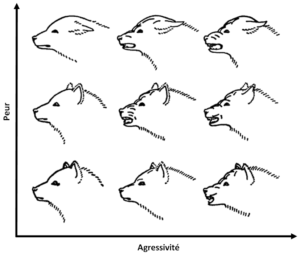

Moving in a border area between fiction and reality, between documentary and fiction, Abounaddara reconstructs the glossy portrait of characters with a horrifying everyday life, which in no case, however, are limited to the expected role of victims. «Our first enemy is pity», said in fact Kiwan in an interview.

In the recent letter opening the seventh issue of the South as a State of Mind, the official magazine of documenta 14, the two publishers Quinn Latimer and Adam Szymczyk, about the work done by Abounaddara, declared: «We believe that the struggle for the ‘right to a dignified image’ […] should be supported».22Q. Latimer, A. Szymczyk, Editors’ Letter, South Magazine, Issue #7.

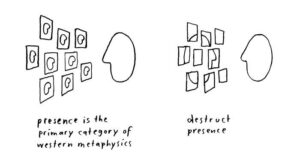

Abounaddara is in fact not looking for pity or compassion, but of what was precisely defined as the right to a ‘dignified image’, cornerstone of the important campaign that in 2011 the collective conducts on the ethical, political and aesthetic levels through its series of short movie and initiatives such as conferences, exhibitions and lectures.

To understand what constitutes a ‘dignified image’, one should just focus on how Abounaddara treats its characters. This can be seen in films such as Children of Halfaya (2013), in which a child describes the gruesome details of the war, the bombs dropped on civilians queuing for bread to the atrocities committed on abandoned and dismembered bodies in the streets. The setting as a backdrop – a tent with basic necessities – reveals a precarious condition and discomfort, but the smiles and laughter of other children present in the scene overturn the terms of these lives in the negative restoring the positive value and inalienable existence.

Or, again, in Without Man (2016) a woman declares herself raised for the death of her husband after having suffered long mistreatment. We do not know who this man was and how he was killed. While talking to him, the woman stops to scold one of his sons: here the banal gesture of a scolding, by stopping the flow of speech, resizes the exceptional nature of the scene, on which there shall be no emphasis.

In each of these videos, a high degree of empathy is perceptible between interviewers and interviewees. Still Kiwan, in this interview of Vice, gives us some indications on the working methods of Abounaddara that well clarify the reasons for this: «We are shooting all the time. We shoot our friends, our neighbours – we are living amongst our subjects. We are not like the correspondents or the filmmakers who come to just shoot and leave. This is our home and our people. […] We listen, we shoot, we look over the footage, and we let our imagination make the rest. […] We are totally free, creatively». Therefore «the explosive charge of liberty» – to use again the words of Calvino – that animates Abounaddara is not so much «in its desire to document, or inform, but in what to express».33Calvino, quoted, p. VII.

Yet Calvino: «To express what? Ourselves, the sour taste of the life we had learned then, many things you believed to know or to be, and perhaps really at that time you knew and were».44Ivi (Same place).

The goal is not in fact to show a truth, but to tell the Revolution while preserving the diversity of points of view and representing the main actor – the Syrian people – without any recourse to emphasis or pathos, widely used, however, in industry media.

Since the outbreak of the civil war, in fact, the Syrian media have codified a precise narrative of the conflict, presenting indiscriminately ‘rebels’ as terrorists and exploiting the images of tortured bodies to mere propaganda purposes. The Western media, however, if on one side were determined to honour the victims of the attacks in France, showing the photographs that portrayed the victims before the massacres, on the other hand had no qualms about spreading sensationalist images of mutilated and lifeless bodies. One example is the case of Alan Kurdi, 3 years old, whose body was photographed on the beach in Bodrum (Turkey) and banged on the front page of every newspaper.

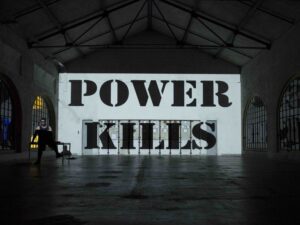

In cases like this, the freedom of the press is inevitably to clash, from an ethical point of view, with the right of the image, for which Abounaddara proposed to add an amendment to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights to recognize it as a ‘fundamental right and inalienable’. About this, writes Abounaddara: «The time has come to seize the weapons of art, cinema and journalism in order to protect society and to allow it to produce its own image beyond power’s grasp. The scales must be shifted in such a way that there is a right to one’s own image that is based on the principle of human dignity and the right to self-determination». The fight for the right to the image hinges on respect for the human and the dignity of the individual self-determination, both violated by a media representation that dehumanizes the victims presenting them as an indistinct mass of ‘bodies’ rather than as individuals.

Bypassing the simplistic polarization, by the media, among the victims, on the one hand, and the perpetrators on the other, Abounaddara therefore shows a portrait far more extensive and complex of the Revolution. In its videos includes men and women of different ages, social classes, political factions and religious affiliations. The narrative never degenerates into clichés, and, despite the short duration, provide the viewer with a sufficiently complete picture of the character’s psychology. Although in the videos it always seriously weights civil war and death, the characters are not portrayed as oppressed, but as men and women that have to deal with and react to an emergency situation. The Abounaddara film creates no victims to be pitied, but rather shows a humanity that, as has been said in this interview, «is the same everywhere, whatever the views of those who defend ‘the complicated Middle East’ and ‘the Syrian exception’». The result is a rich human samples that preserves the individuality, but whose full value is expressed in its choral polyphony and, as was also noted by C. Lange of Frieze: «These are films that are absorbed slowly – their power accumulates through aggregation».

Taking place on the level of representation, the battle of Abounaddara for recognition of the right to a ‘dignified image’ inevitably involves various aspects, from the aesthetic to the political, legal and ethical, thus taking shape as an achievement that mankind must necessarily obtain: «Our position is based on arguments that are aesthetic (death in close-up offers no more information about a crime than pornography does about love), political (Syrians are not victims of a natural disaster, but men and women who are fighting for an ideal of freedom and dignity), legal (individuals’ rights to their images must be respected in all circumstances), and ethical (pity is dangerous, especially when it is preached by a media with a vested interest in disseminating sensationalist images55A. Mayyasi, A new kind of weapon in Syria: Film, interview, «The Brooklyn Quarterly».

)».

More on Magazine & Editions

Digital Library

La Mia Morte

Un racconto polifonico degli ultimi istanti di vita di Pier Paolo Pasolini.

Magazine , LINGUAGGI - Part I

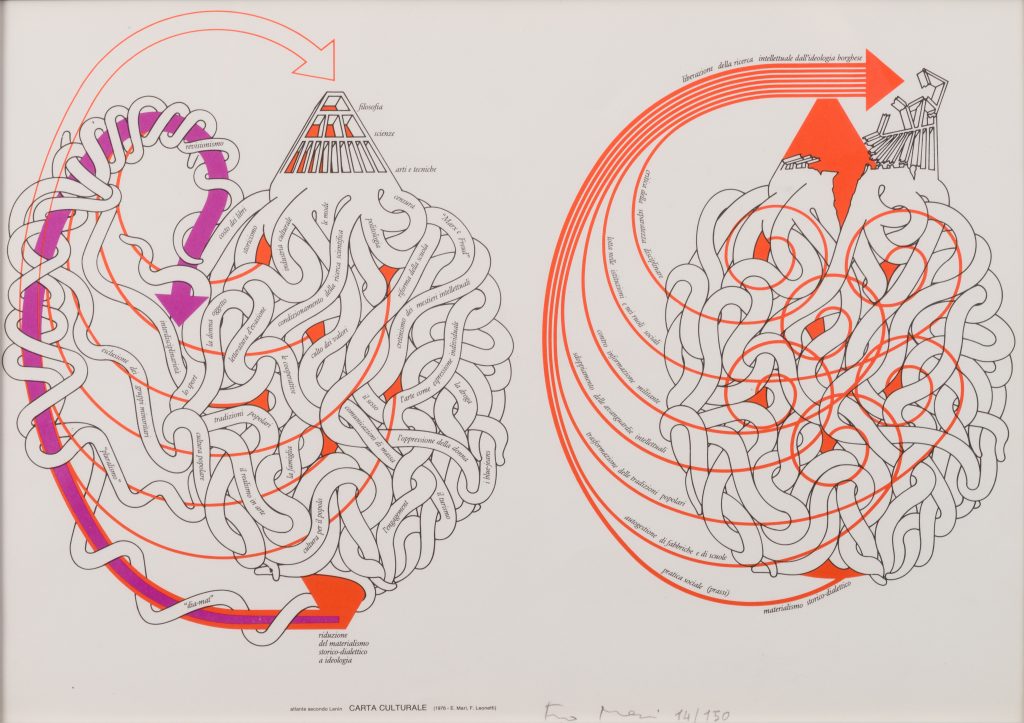

L’editoria indipendente italiana all’indomani della rivoluzione mediatica

Zine della controcultura giovanile e gatekeeper dell’arte contemporanea.

Editions

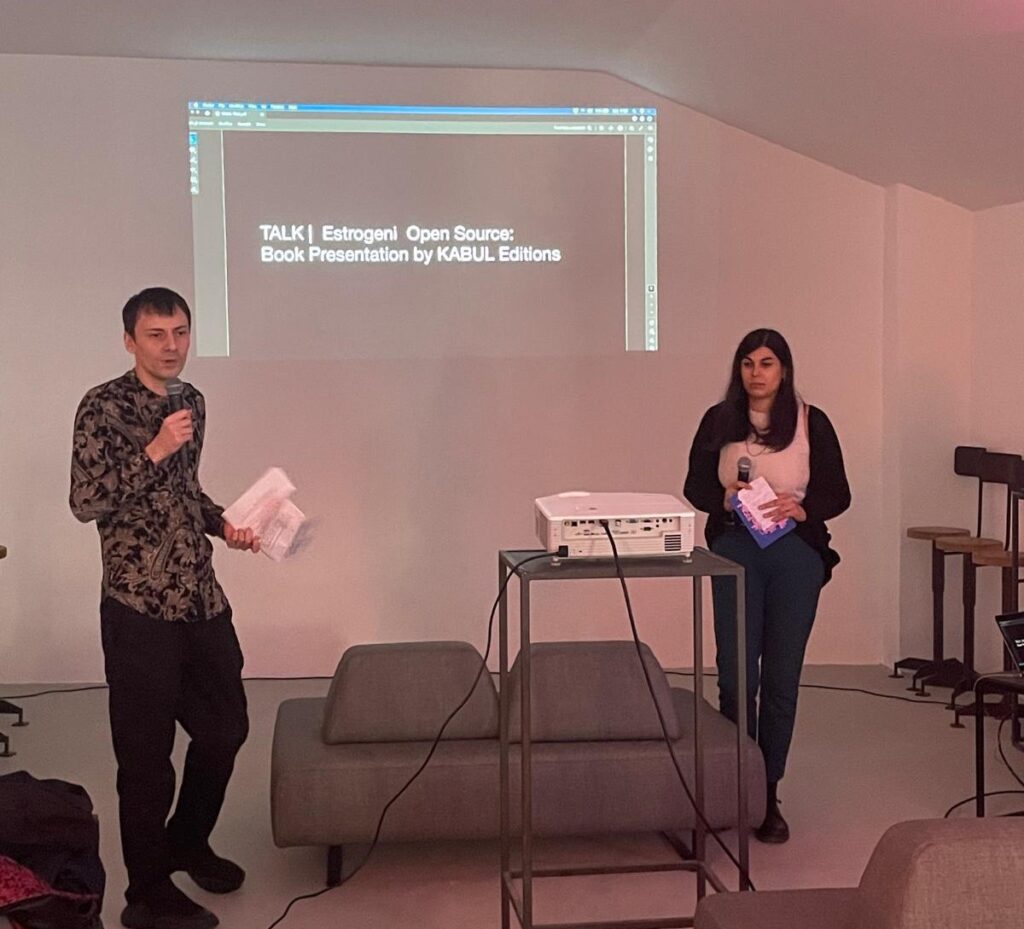

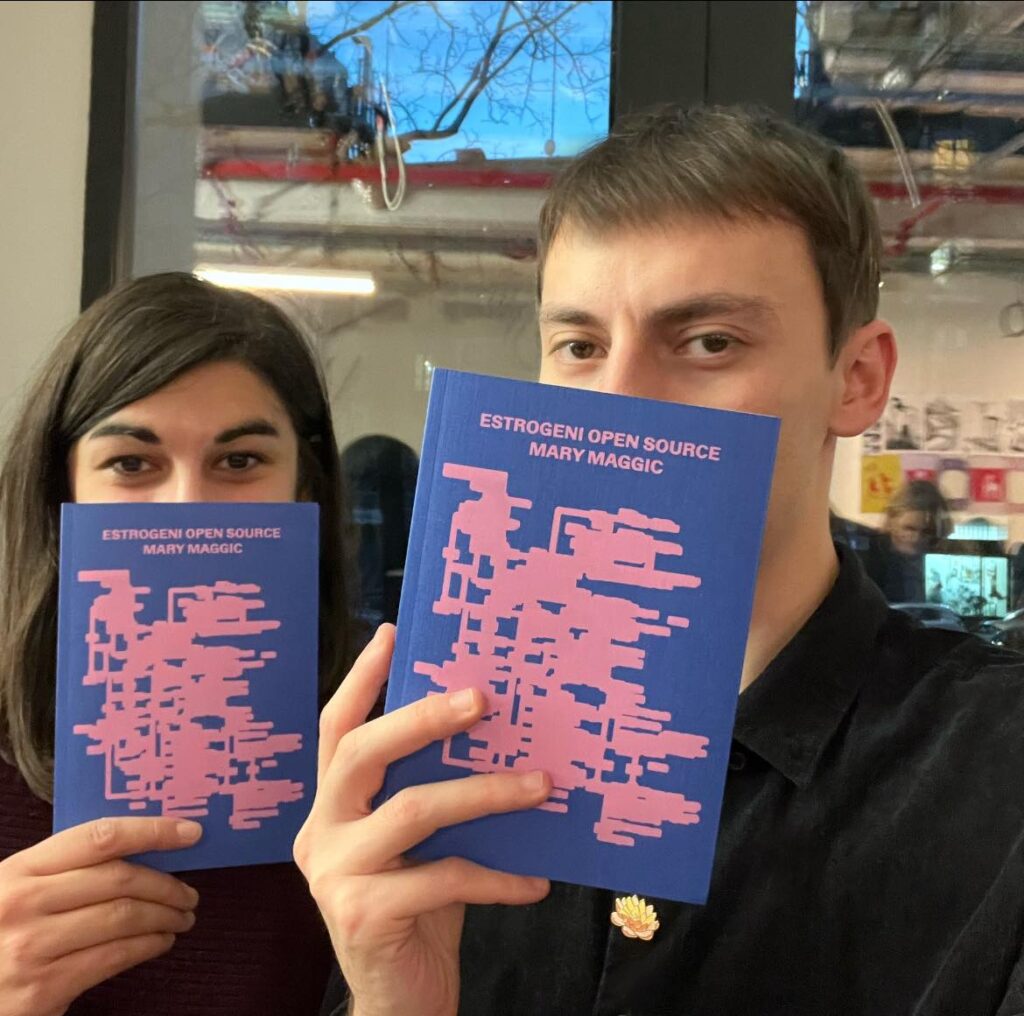

Estrogeni Open Source

Dalle biomolecole alla biopolitica… Il biopotere istituzionalizzato degli ormoni!

Editions

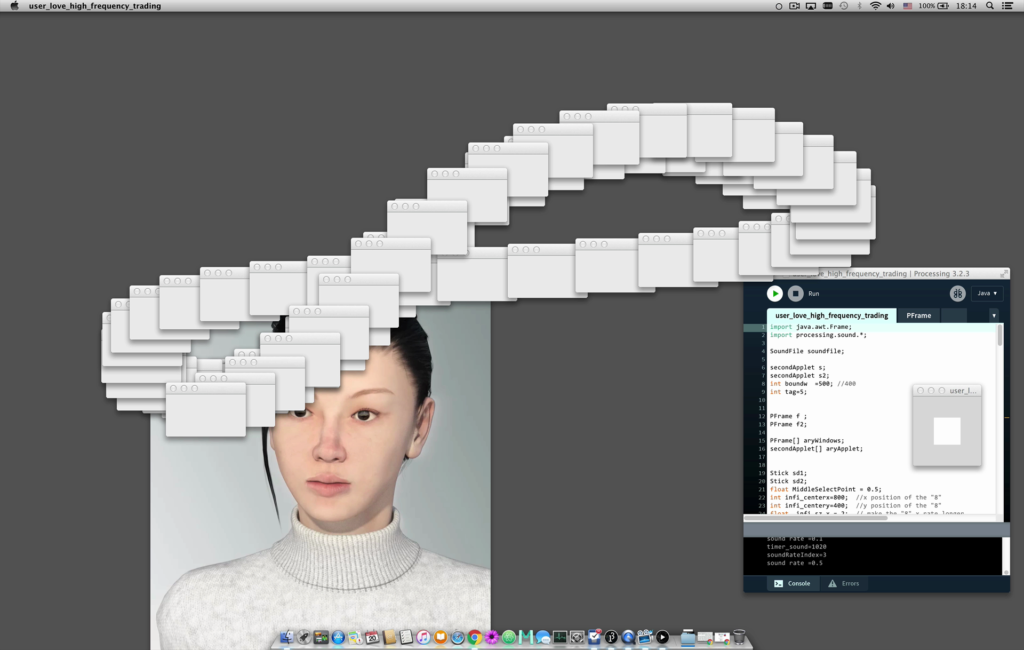

Embody. L’ineffabilità dell’esperienza incarnata

Il concetto di coscienza incarna per parlare di alterità e rivendicazione identitaria

More on Digital Library & Projects

Digital Library

La Mia Morte

Un racconto polifonico degli ultimi istanti di vita di Pier Paolo Pasolini.

Digital Library

Dalla visione del mondo alla sua esposizione

La favola di Internet come esposizione mondiale d’arte universalmente inclusiva e la figura dell’artista contemporaneo da artefice della forma a fornitore di contenuti. In esclusiva su KABUL magazine, un saggio inedito del 2018 di Boris Groys.

Magazine , PEOPLE - Part I

La grande abbuffata: dall’Ultima cena al food porn (#artissimalive)

The Edit Dinner Prize: il rapporto tra arte e cibo tra storia dell'arte e ossessioni culinarie contemporanee.

Projects

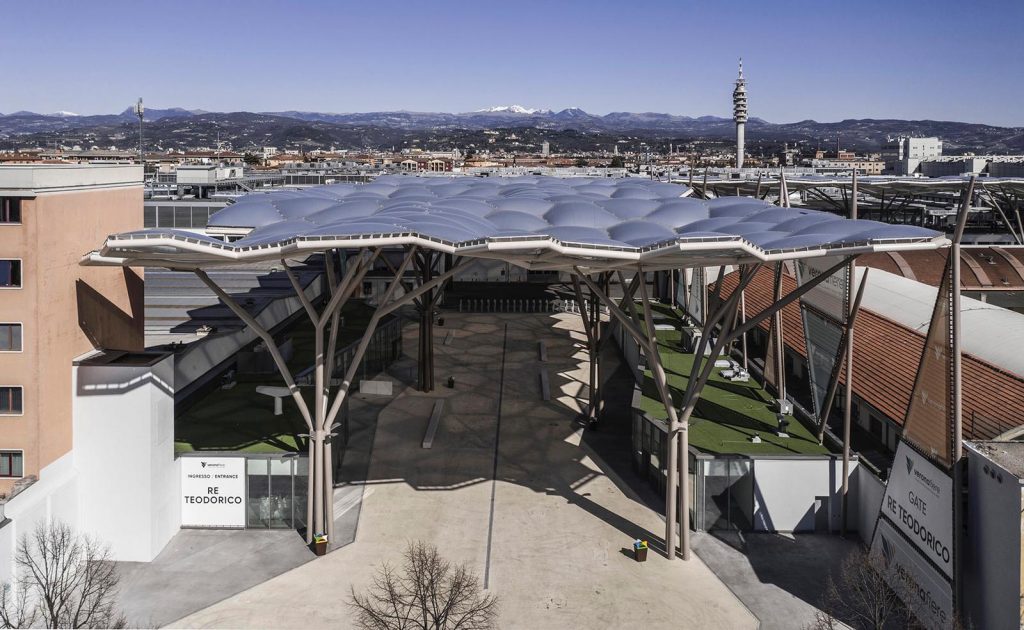

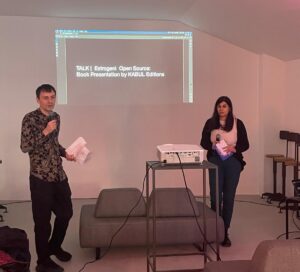

KABUL ft. MEGA Art Fair 2025

Un enorme grazie a tutte le persone che sono passate a trovarci da MEGA Art Fair 2025 di Milano. In questa occasione abbiamo presentato il nostro libro, Estrogeni Open Source.

Iscriviti alla Newsletter

"Information is power. But like all power, there are those who want to keep it for themselves. But sharing isn’t immoral – it’s a moral imperative” (Aaron Swartz)

-

Dario Alì è Responsabile didattico per Formazione su Misura (Mondadori Education – Rizzoli Education) e Direttore editoriale di KABUL magazine. Dopo aver conseguito una laurea magistrale in Filologia della letteratura italiana, partecipa a CAMPO (Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo) e ottiene un master in Editoria cartacea e digitale presso l’Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore. È autore, per De Agostini, di due volumi biografici su Torquato Tasso e Lorenzo Valla. Attualmente vive e lavora a Milano.

I. Calvino, Il sentiero dei nidi di ragno, Mondadori, Milano 1964.

SITOGRAPHY

Abounaddara, An Ideal, or We Will All Die, «documenta 14», 20 Nov. 2015.

Abounaddara, Syria: We Are Dying, «Zeit Online», 30 Apr. 2016.

C. Boëx, Un cinéma d’urgence, «La Vie des idées», 25 Sept. 2012.

L. Feinstein, This Syrian Filmmaking Collective Shows the Banality of Life in War, «Vice», 24 June 2015.

C. Lange, Emergency Cinema, «Frieze», 18 Mar. 2016.

Q. Latimer, A. Szymczyk, Editors’ Letter, South Magazine, Issue #7.

A. Mayyasi, A new kind of weapon in Syria: Film, interview, «The Brooklyn Quarterly».

M. Ryzik, Syrian Film Collective Offers View of Life Behind a Conflict, «The New York Times», 18 Oct. 2015.

M. Serafini, Trasfusioni, droga, torture e stupri: voci da Raqqa, la capitale del Califfato, «Corriere della Sera».

D. Zabunyan, Le droit à l’image est-il égalitaires?, interview, «Artpress», n. 41, May-July 2016.

KABUL è una rivista di arti e culture contemporanee (KABUL magazine), una casa editrice indipendente (KABUL editions), un archivio digitale gratuito di traduzioni (KABUL digital library), un’associazione culturale no profit (KABUL projects). KABUL opera dal 2016 per la promozione della cultura contemporanea in Italia. Insieme a critici, docenti universitari e operatori del settore, si occupa di divulgare argomenti e ricerche centrali nell’attuale dibattito artistico e culturale internazionale.